The Second Instrument

The Double Exposure: Musicians Who Frame the World Through a Lens

B.B. King Bill King Photography

A camera in the hands of a musician isn't an accessory—it's an extension, like a muted horn or a slide slipping into place. It's not just gear; it's gearshift—transporting what's felt in the gut and fingered in the dark into something seen. Tangible. Permanent.

You learn early on that the same instincts that tell you when to drop the chord also tell you when to hit the shutter—timing, space, restraint. The rest is just light and waiting.

When I first picked up a camera with serious intent, the most challenging part wasn't f-stops or shutter speeds. It was people. Human beings. Their eyes. Their defences. Pointing that lens at someone felt like opening a door; I wasn't sure I had the right to walk through. You ask yourself: What gives me the right to record this moment? The truth is, it's not about rights. It's about the weight of intention. It's about trust. About learning to disappear behind the lens and reappear in the frame with soul.

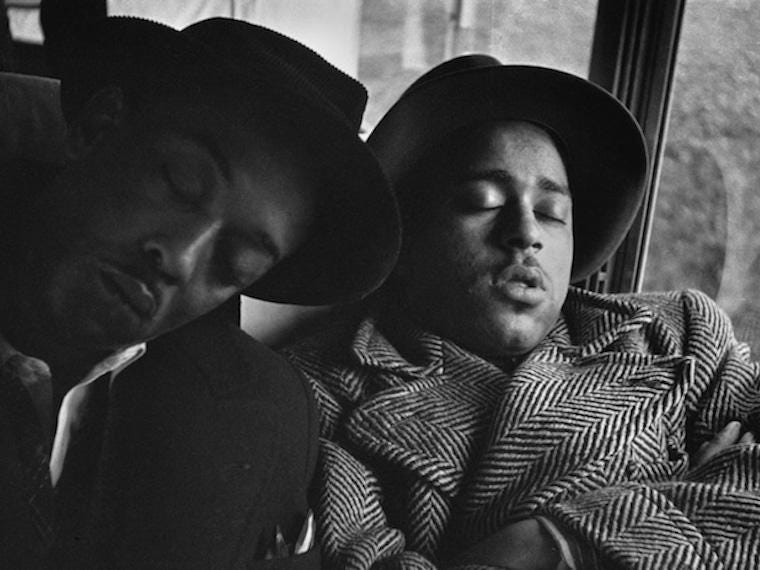

Jazz bassist Milt Hinton knew this. Better than anyone. That cat swung low with his bass and high with his Leica. His lens didn't just document jazz—it understood it. He didn't shoot performances; he shot proximity—sweat between sets. Ties loosened. The joke's cracked. Shoes off, eyes closed, hand still twitching in rhythm. You could feel the tempo in those images, like a walking bass line snapping underfoot.

Milt Hinton Photography

And Oscar? Peterson wasn't just about touch on keys—he understood the slow, chemical magic of the darkroom. He had the Leica. The colour setup. The silence. But humility held his prints hostage. When I asked to showcase them in Jazz Report, he said they weren't good enough. But I knew better. The man walked among kings and queens of tone and time. What he captured, even shyly, would've been masterclass material. He saw the invisible.

Then you pan out—look at the broader stage.

Bryan Adams drops the guitar pick and picks up a medium-format Hasselblad. And wouldn't you know it? He frames people the way he frames songs. Honest. Unpolished. Amy Winehouse caught in that exhale between defiance and despair. Queen Elizabeth not as a monarch but as a moment. He doesn't flatter. He listens with the camera.

Bryan Adams Photography

Patti Smith—what can you say? Her Polaroids are whisper-prayers. Rooms with ghosts. She photographs silence as if it were a living thing. A pair of boots. A window. A bed that once held Rimbaud's dreams. Each image aches like a leftover chord at the end of a requiem.

And Lou Reed—no polish, no pretense. Just grain and grime and truth. His photos didn't need captions. They were captioned. He shot New York as he lived it: straight to the bone like Berlin, but on paper.

Lenny Kravitz always sculpts with shadow and sweat. His black-and-whites aren't quiet. They hum. They vibrate. That's muscle memory. That's funk turned visual.

Lenny Kravitz

Graham Nash, meanwhile, pulls the volume back. His photos have the hush of a fading harmony. A glimpse of Joni by windowlight. A chair in shadow. His work speaks in undertones but never without weight.

Courtney Love? She's a raw nerve. Her photos are like her vocals—sharp-edged, bleeding, and alive. No filters. No edits. Just flash and fury.

What connects them all? It's not a celebrity. It's a compulsion. That needs to say something, even when the music stops. You don't escape sound with photography—you follow it. Extend it—a new form of improvisation. The lens becomes a bridge between what is played and what is seen.

And in jazz, that bridge was always waiting.

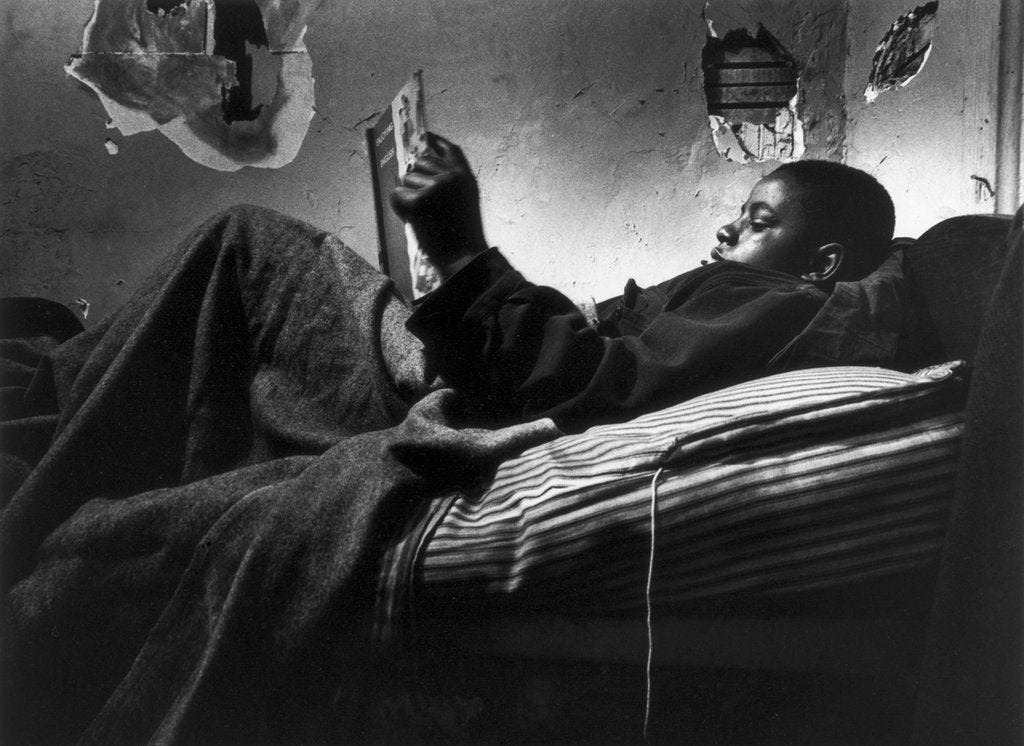

Mingus didn't just compose; he composed visually. Frames full of energy, never symmetry. That was his gospel—a wild harmony of motion and blur. Dolphy caught in a moment of sonic levitation—like Mingus was sketching a solo with light instead of ink.

Gordon Parks Photography

Even Monk—those lost Polaroids—what I wouldn't give to see them. You know they'd be slanted and soulful. Quirky genius is embedded in each frame. Parker's Contax? Pawned, maybe. However, in the mythology of the moment, those unseen images persist. Smoke curling around a brass bell. Laughter caught between choruses. Shadows on a wall keeping time.

These weren't tourists. These were insiders. Architects of the unseen. They knew the code—the moment before the downbeat, the instant just after the phrase lands. They photographed not around jazz but within it.

Albert Murray had it pegged—the visual blues. That syncopated soul caught not in soundwaves but in the split second between aperture blades. Hinton's stash. Mingus's lens jabs. A legacy carved from negatives and contact sheets. No mythology, just memory. No mythmaking, witness.

Bill King Photography Havana 1998

We don't just see music in those photographs—those double exposures of heart and eye. We feel its breath on the back of our necks. We walk into the room. We hear the cough before the solo. We see the stoop on a genius's shoulders. We get to be there—not in front of the stage, but beside it. Backstage. Basement. Balcony. One shutter clicks from eternity.

That's the gift. That's the groove. That's the second instrument speaking.

I started with a Yashika 35. Pentax, Nikon, Canon and the past 15 Lumix. Own a Fuji TX 30. Still trying to get with it.

And mine was the Cannon TX. First SLR. Film of 24 or 36 roll that taught me to really look for that perfect shot. Shots that would have to wait until the end of the roll, and being developed.

When you opened those pictures up is when you knew if you got it. And occasionally you did.

It has made a better eye for me.