There was a time when the living room wasn’t dominated by flickering screens or the passive hum of a streaming playlist. Instead, it was a place of gathering, where music—real, resonant, and tactile—poured from an instrument as grand as the era itself. The player piano, a marvel of late 19th and early 20th-century ingenuity, stood as a testament to both human artistry and mechanical brilliance. At its heart was the piano roll, a perforated strip of paper that carried the imprint of a pianist’s soul, guiding wooden hammers and felt-covered keys through a performance that felt almost—almost—alive.

The idea of mechanized music had been toyed with for centuries. From the intricate mechanics of barrel organs to the elegant automata of the 18th century, humans had long sought to capture and reproduce sound through ingenuity. But it wasn’t until the 1870s that the concept found its full flowering in the player piano. These self-playing instruments, guided by rolls of punched paper, could render complex compositions with precision, bringing the concert hall into the parlours of the middle class.

At first, these rolls functioned much like a rudimentary MIDI file—triggering notes but lacking the expressive touch of a human hand. But as the technology evolved, so too did its capabilities. By the early 20th century, reproducing pianos like the Welte-Mignon, Ampico, and Duo-Art could capture the subtlest nuances of a performance: the feather-light touch of a Chopin prelude, the boisterous stride of a Jelly Roll Morton rag, the weighty contemplation of a Rachmaninoff etude. These weren’t just mechanical interpretations of sheet music; they were ghostly echoes of the past, a means by which a listener in 1925 could sit in their drawing room and hear Gershwin himself roll through a lively “Rhapsody in Blue.”

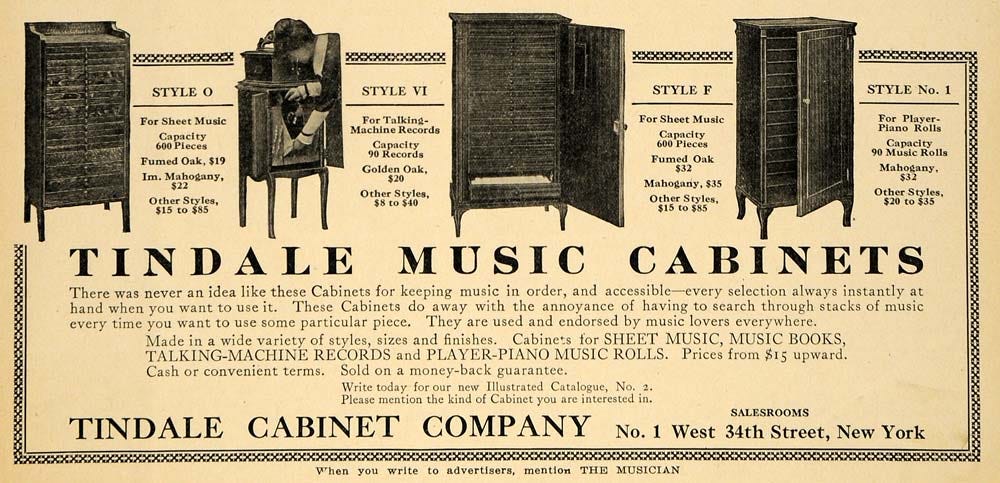

At a time when the phonograph was still an emerging technology, and radio had yet to dominate, the piano roll democratized music in a way few innovations had before. In cities and small towns alike, one could walk into a music shop and purchase the latest hit—be it a lilting waltz, a swinging fox-trot, or a brassy jazz tune—and bring it home, where the keys of their player piano would dance in perfect synchronization. Families gathered around these mechanical maestros, much like they would later do around the radio or television.

This was also an era of musical cross-pollination. Ragtime, blues, and early jazz made their way into American homes, influencing generations of musicians who might never have set foot in a juke joint or vaudeville hall. The likes of Scott Joplin and Fats Waller found their music travelling far beyond the smoky clubs where they performed, immortalized in a cascade of black dots and perforations.

Yet, as with all technological marvels, the piano roll had its time and then fell into the shadows. The 1930s ushered in the phonograph as the dominant means of recorded music, and with the advent of radio, the need for player pianos waned. By the time the post-war years rolled around, the once-ubiquitous rolls were relics of another age, gathering dust in antique stores and forgotten attics.

But the past has a way of whispering to those who listen. The 1960s saw a renewed interest in piano rolls, driven by collectors and musicologists who recognized them for what they were: invaluable artifacts of a bygone era. As digital technology advanced, scholars and musicians found ways to convert these perforations into data, reanimating performances from a century ago with startling clarity. Modern reproducing pianos, such as the Yamaha Disklavier, could play back these rolls with stunning fidelity, allowing us to sit in awe as Rachmaninoff himself caresses the keys, as if time had never intervened.

Today, the piano roll is more than curiosity; it is a bridge across time, a conduit for the voices of pianists long past. In an age where digital files can be edited into perfection, there’s something profoundly human about these rolls—flawed, tactile, alive with the energy of an artist at the moment. They remind us that music is not just about notes on a page or waves in the air, but about connection—between past and present, between hands and hammers, between the living and the long gone.

For those willing to listen, the perforations still sing.

There is. It’s digital. You can use Alexis commands.

Loved the piece on piano rolls. Did you know there's still a company (located in Buffalo, I think, but don't hold me to that), that still makes and market piano rolls — the laat buggy-whip manufacturer! You can check their website, www.qrsmusic.com. What was that song? "Everything old is new again"?