If there’s a word to encapsulate Carl Perkins, it’s “understated.” Not in talent—he had that in spades—but in the way he carried his music, like a whisper that spoke volumes. Perkins wasn’t just a pianist; he was a painter of harmonies, a subtle architect of mood, and a master of understatement. Perkins turned what might have been a limitation into profound sensitivity, letting every note breathe life into the next. The left arm, shaped by a battle with polio, hovered parallel to the keys, a poised counterbalance to the melodic right. The elbow, unorthodox yet masterful, would descend upon the deep bass notes, conjuring sounds that reverberated with the weight of resilience.

Each note he struck seemed to tell a story—a defiance of limitations, a rewriting of the rules. The rhythm he crafted wasn’t just music; it was a conversation between will and creativity. In those deep, resonant bass lines, you could hear not only his determination but the triumph of art over adversity.

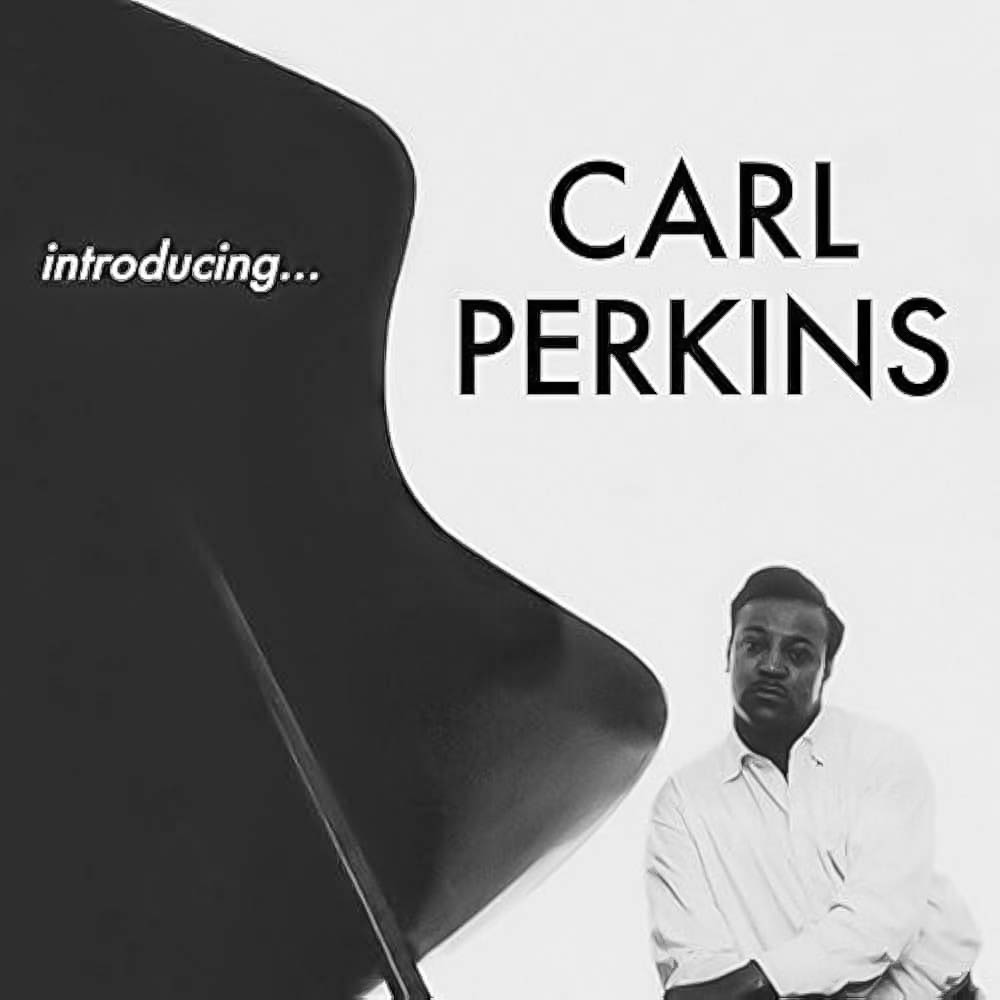

I stumbled across Carl Perkins’ playing on YouTube the other day, guided by the voice of a narrator passionately advocating for this quiet genius—a pianist who, despite his brilliance, remains largely unsung. The cover of Introducing Carl Perkins tells its own story. There he is, perched at the piano, his expression a blend of shyness and warmth, as though he’d rather let the music do the talking than posture for the camera.

Then came “Grooveyard.” From the first note, it was clear I was in the presence of something rare. Perkins didn’t just play chords; he painted them, each one a carefully chosen hue on his harmonic palette. His touch was as light as a whisper, his phrasing as natural as breath, yet there was an undeniable weight beneath it all—a depth born not just of musical sophistication, but of life lived and challenges weathered.

Every phrase seemed to float, suspended in time, swinging not with bravado but with grace, like the way a leaf dances in the wind. And somewhere in that quiet elegance, you could hear his story—triumphs, struggles, resilience. Perkins didn’t demand attention; he earned it, note by note, with a humility as rare as it is beautiful. It’s the kind of playing that reminds you why you fell in love with music in the first place.

Born in Indianapolis in 1928, Carl Perkins lived through an era of seismic change in jazz. He played alongside titans like Dexter Gordon and Chet Baker, holding his own in ensembles as volatile as they were brilliant. The West Coast scene, often dismissed as "cool" or "laid-back," found in Perkins a soul who could bridge its easy elegance with the heartfelt grit of the Midwest.

What separated Perkins from many was his phrasing—a singular approach that danced somewhere between Bill Evans’s introspection and Horace Silver’s earthiness. His playing on “Way Cross Town,” with Art Pepper, showcased a rare ability to accompany without overshadowing, to lead without overpowering. Perkins found the cracks in the music where emotion seeped through. It was the slant in the fingers, almost Monk like attack that kept me fixated on the keyboard. Polio affected Carl Perkins during his childhood, which left him with a withered left arm. Despite this physical limitation, Perkins developed a unique playing style that allowed him to use his left hand effectively, often incorporating intricate voicings and rhythmic patterns.

Tragically, Carl Perkins didn’t live to see his prime. He died at just 29 in 1958, a victim of heroin addiction—a scourge that claimed too many brilliant musicians of his era. The jazz world mourned a loss that felt unfinished, a book with too few chapters.

But in the fleeting moments he gave us, Perkins’ music lives on—a reminder that you don’t have to shout to be heard. His melodies still hang in the air like a conversation with an old friend, intimate and enduring. And perhaps that’s the most profound legacy of all. Perkins played as if he knew life’s fragility, and in doing so, he gave us something timeless.