I was born within spitting distance of the Ohio River—close enough to taste the tannin-soaked wind that rose off its surface and to watch the barges crawl past like weary pilgrims headed for redemption or ruin. Pops bought a cabin cruiser once—a proud but battered husk of a boat—which he perched on cinder blocks in a neighbours backyard like some fallen monument to adventure. He patched the hull with hardware store sealer and a prayer, the launch a game-changer. For me, that was enough. The river was close, and it had a voice.

That voice wasn’t soft. It whined through calliopes, howled through foghorns, and whispered in the splash of driftwood and dreams gone sideways. You learned young in Jeffersonville that the Ohio didn’t give you romance. It gave you rhythm and ruin. It showed you the soft glow of bourbon parlors and the bruised knuckles of men who lost more than they could ever earn back. It carried your secrets downstream.

Eighteen years ago, my hometown handed me the Commander of the Port award for “international contributions to the arts.” I was humbled. But truth be told, that citation—however fine—only reaffirmed something I’d always known: that my life, my music, my compass, all pointed back to this river. Back to a town where gamblers once lined the levee, where moonshine slipped through the night like a hymn, and where madams held more sway than the mayor.

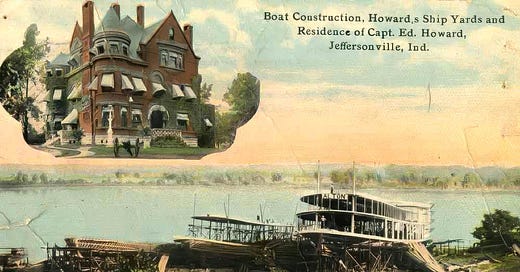

Jeffersonville in the mid-1800s wasn’t some sleepy Midwestern outpost—it was a hotbed of vice with a backbeat. The paddlewheelers came rumbling in like floating carnivals, stacking deckhands and hustlers alongside horn players and snake-oil men. The “Line”—our red-light district—ran just a few blocks inland, a row of brothels and gin joints where fortunes evaporated between cards and kisses. Louisville glared at us across the water, jealous or ashamed, but they came all the same.

I remember Pops pointing out the hobos and makeshift tents along the midstream islands. “That’s what the river does, son,” he said. “It gives a man movement, not always direction.” And as the current pulled at the bones of bleached-out driftwood and broken crates, I realized he was right. Jeffersonville was a town of passers-through and passers-on. And yet, something in the silt stuck to your soul.

Music was everywhere—jammed in between the riverboat jazz and the ragtime piano pounding from saloons, skimming in from Louisville and burrowing into every backroom and beer hall. We bred jug band pickers, barrelhouse shouters, and gospel-tinged sirens who knew the blues like scripture. We played to the river, and it answered with thunder.

And that river—well, she runs long. From Pittsburgh to Cairo, she ties together a musical heritage that’s as diverse and tangled as the roots of a willow tree half-swallowed by her muddy banks. The Ohio River is a mother to many:

In Louisville, it birthed Lionel Hampton, a boy who took jazz to the skies with the vibraphone, and Joan Osborne, who spun gospel truths into mainstream hymns. Across the levee in Cincinnati, Bootsy Collins thumped the bass with cosmic funk, while James Brown, though Carolina-born, cut his teeth at King Records, defining a sound that roared up and down the river like gospel on fire.

Evansville gave us Gretchen Peters, whose songs bleed with truth, and Huntington laid the early roots for Michael W. Smith and Hazel Dickens, whose voices rose like prayer from the Appalachian hills.

Pittsburgh, where the Ohio is just beginning to stretch her legs, gifted the world George Benson, Art Blakey, and Billy Eckstine—giants who made jazz bend, break, and rise again. And down near Portsmouth, Bobby Bare sang about the hard corners of river life with a voice as weathered as a steamboat hull.

At the mouth in Cairo, where the Ohio empties its stories into the broad-chested Mississippi, the names may not be famous, but the influence is—bluesmen and gospel singers catching the river’s last whisper before it vanishes into Delta myth.

And so I carry the river with me. In every piano note I strike, in every photo I frame, in every story I write, there’s a bit of driftwood caught between the keys. Jeffersonville gave me more than an award—it gave me my compass and my contradictions.

Because we’re all children of the river, aren’t we? Born in the eddies, baptized in the mud, raised on bourbon, brass, and the sound of something just around the bend.