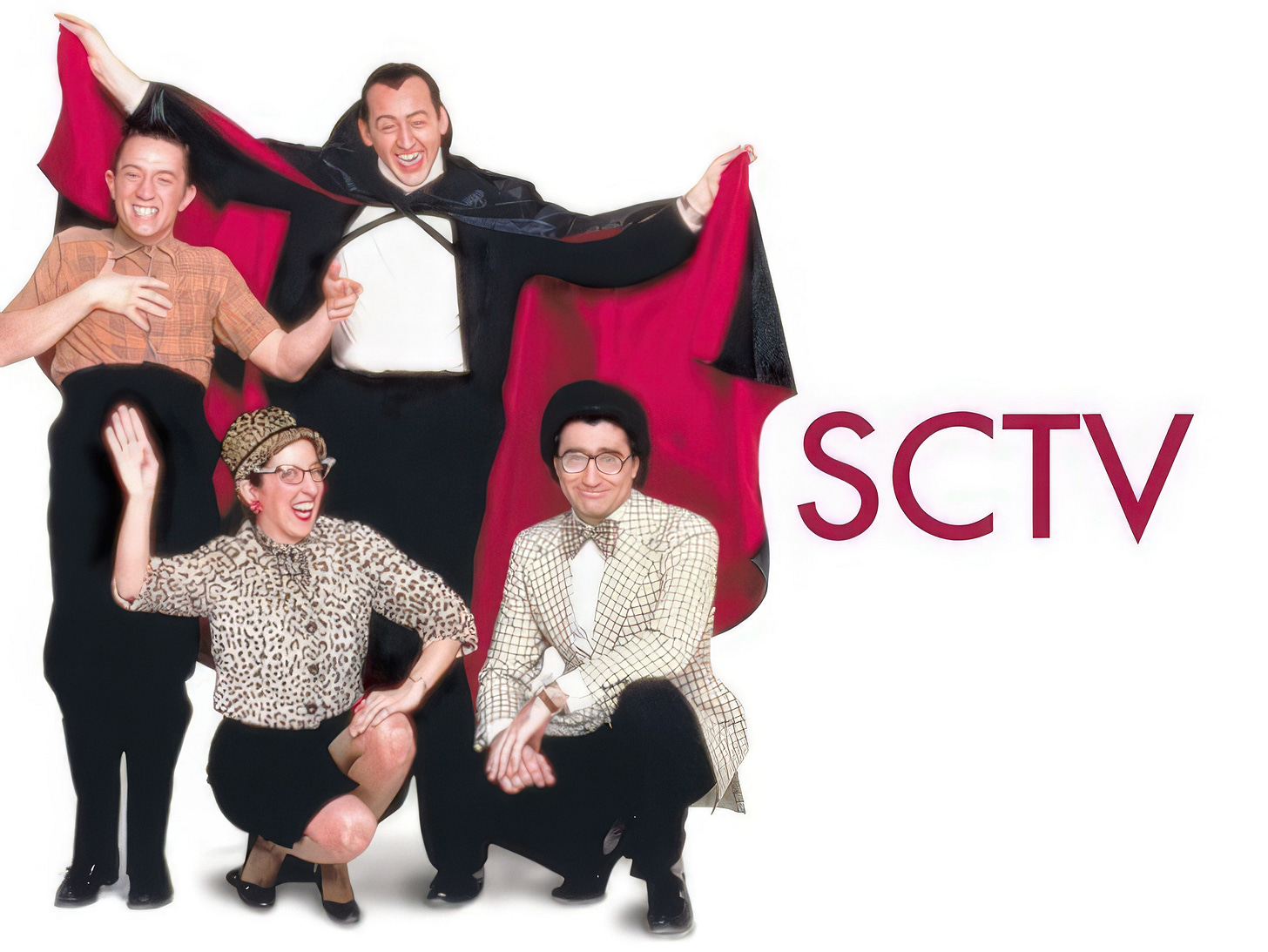

Watching old SCTV reruns on YouTube is like rediscovering a lost art form—comedy that was meticulously crafted, deeply weird, and still gut-wrenchingly hilarious decades later. It doesn’t just hold up; it thrives in the rewatch, revealing layers of brilliance you might have missed the first time around. The same can’t always be said for SNL, which often feels like flipping through old newspapers—occasionally interesting, but mostly a reminder of how fleeting topical humour can be.

What makes SCTV endure? Commitment. To the bit, to the character, to the absurdity of television itself.

SCTV was the kind of comedy that sneaks up on you—subversive, off-kilter, and strangely sophisticated, even when it was utterly ridiculous. It didn’t just riff on pop culture; it deconstructed it with surgical precision. Where SNL felt like a frantic race to get a laugh before the cue cards ran out, SCTV took its time building worlds inside a fictional television network that felt absurdly real.

John Candy’s Johnny LaRue, a tragic figure obsessed with getting the elusive crane shot, was pure brilliance—equal parts Hollywood hack and desperate dreamer. Eugene Levy and Catherine O’Hara could disappear into characters so deeply you forgot they weren’t real people. Rick Moranis as Merv Griffin, Joe Flaherty as Count Floyd, Andrea Martin’s hypercharged Edith Prickley—every one of them delivered comedy that wasn’t just funny, it was layered.

The genius of SCTV was that it never pandered. It assumed you were in on the joke, that you recognized the absurdity of television itself. The soap opera sendups (The Days of the Week), the late-night horror host parody (Monster Chiller Horror Theatre), the commitment to running gags—it was a comedy nerd’s paradise.

SNL had its moments. But SCTV? That was where the real comedy lived.

There’s a reason SCTV still holds up, while so much of SNL feels like an artifact of its era. It’s the difference between crafted satire and disposable sketch comedy. SCTV wasn’t just chasing the next laugh—it was building a universe, a fully realized, brilliantly absurd world inside the confines of a struggling TV station.

Where SNL was always shackled to the moment—topical, reactionary, and often dated within a week—SCTV played the long game. Its comedy wasn’t tied to political cycles or celebrity scandals; it was rooted in character, in the absurdities of show business, in the quirks of human ambition. Johnny LaRue’s desperate need for respect, Count Floyd’s struggle to make 3D horror sound terrifying, Bobby Bittman’s smarmy showbiz ego—they weren’t just sketches, they were full-fledged studies in comedic character work.

Even the parodies had more weight. SNL might do a quick-hit impersonation, but SCTV would take a deep dive. Their take on Godfather (Maudlin’s Eleven) wasn’t just a throwaway bit—it was an entire alternate reality where Sammy Maudlin was caught up in mob dealings. The Great White North wasn’t just a goof on Canadian stereotypes; it became a pop culture phenomenon on its own terms.

And then there was the craftsmanship. SCTV had structure, visual gags, running storylines. It wasn’t just actors standing on a stage reading cue cards. It was cinematic, deeply weird, and often, hilariously subtle.

That’s why it still works. SCTV wasn’t trying to ride the zeitgeist—it was too busy creating its own.

The Canadian cast members of SNL—from Dan Aykroyd and Martin Short to Mike Myers and Norm Macdonald—carried with them a distinct comedic sensibility shaped by their northern roots. It’s no coincidence that many of them either passed through or were directly influenced by SCTV, which had already proven that Canadian humour was sharper, weirder, and more character-driven than the broad, topical fare often found on SNL.

Dan Aykroyd set the tone early, bringing a rapid-fire, almost intellectual approach to absurdity. His brilliance lay in how he could take something completely ridiculous and deliver it with absolute sincerity—whether it was the hyper-technical gibberish of the Bass-O-Matic pitchman or the sheer conviction behind his portrayal of Elwood Blues. That straight-faced commitment to the bit? That’s pure SCTV DNA.

Then there’s Martin Short, who brought a level of precision and physicality rarely seen on SNL. His characters—Ed Grimley, Jackie Rogers Jr.—were so fully realized, so deeply embedded in their own strange little worlds, that they felt lifted from SCTV’s playbook. Short understood what SCTV had mastered: great comedy isn’t just about the punchline—it’s about the person delivering it.

Mike Myers took it a step further, blending his love for British comedy with the Canadian ability to lampoon American pop culture from the outside looking in. Wayne’s World, Coffee Talk, Dieter’s Sprockets—these weren’t just impressions or one-off jokes; they were immersive comedic environments, each with their own logic and rhythm. You can draw a straight line from Bob and Doug McKenzie’s Great White North to Wayne’s World—both took minor, offbeat sketches and turned them into cultural phenomena.

And then there’s Norm Macdonald—one of the greatest Weekend Update anchors in SNL history. His style was pure Canadian irreverence: bone-dry, deeply sarcastic, and completely unafraid to bomb if it meant staying true to the joke. His relentless O.J. Simpson barbs got him fired, but they also cemented his legacy as one of the most fearless comics in SNL’s history.