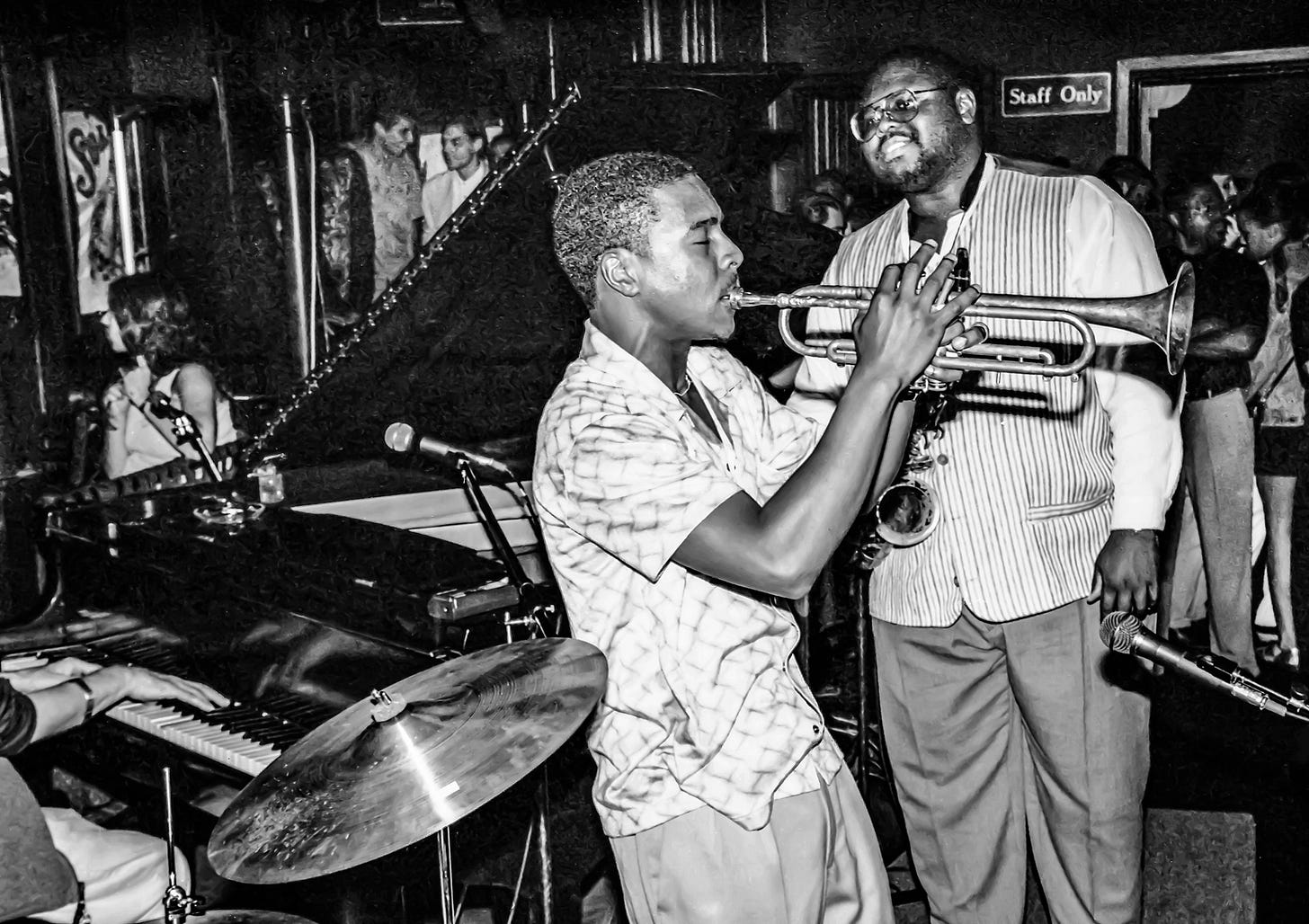

Photography Bill King

There’s no jazz musician I have seen perform—or photographed—as many times as Roy Hargrove. No one. Not Marsalis, not Brecker, not Redman. Not even the saints of the saxophone or the prophets of piano. Hargrove was the pulse of a generation and the punctuation of a lineage that began with Armstrong’s growl, ran through Clifford’s fire, Lee’s bluesy burn, and Miles’s cool suspicion. But Roy was different. He was all of that and something we hadn’t quite named yet—maybe never will.

When the documentary Hargrove recently surfaced on YouTube, I did what any man who’d once shared a hallway with the legend might do: I sat down. No distractions. Lights low. Heart open. The film, directed by Eliane Henri, is a raw and vulnerable portrait of Hargrove in his final year—2018—a year still blowing, still stubborn, still magical. It follows him across Europe, through nightclubs, clinics, dressing rooms, alleyways, back onto stages, into dialysis appointments and himself.

I’ve lived on both sides of this story. I've spoken with booking agents who are desperate for predictability. I’ve been inside the eye of the storm with manager Larry Clothier, a man whose devotion to Roy was matched only by his constant exasperation. I’ve sat with the ever-elegant Italian vocalist Roberta Gambarini, Roy’s friend and musical partner, watching her navigate the chaos with grace and concern. Together, Kristine and I spent time with Larry and Roberta. I remember Larry’s voice—tired, cracked, half laughter, half plea—speaking of dialysis schedules missed, hotel rooms gone dark, gigs that nearly didn’t happen, and the body that Roy seemed to forget he was still living in.

We featured Roy on the cover of Jazz Report Magazine in 1992. That wasn’t just ink and glossy paper—it was a statement. We made posters of that cover and wallpapered downtown Toronto with them, knowing he was set to perform at the DuMaurier Downtown Jazz Festival in Yorkville. Roy, forever unpredictable, blew into the city like a warm front colliding with a cold one—brilliant and dangerous. After hours, we trailed him to the Colony Hotel, where the authentic jazz always lived, in those humid late-night jams, sweat and spit valves and unrehearsed miracles. Roy and Roberta were constantly moving, from Toronto to St. Lucia to Barbados—touring like two apostles of the sacred groove.

We even crossed paths in Moscow, Idaho—of all places—at the Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival. There’s a hallway memory I hold dear. I’m seated with the ageless vibraphonist Terry Gibbs. No vibes in sight, so Terry sits at the piano beside me, pounding like he’s got mallets for fingers. I’m walking the bass line, holding it steady. In walks Roy, dreadlocks swinging, that trademark half-smile barely visible beneath his thoughtful eyes. He nods, maybe mumbles something—who knows what—but says more with that look than most musicians can with an hour of scales. Then he disappears.

And isn’t that what Roy did best? Appear just long enough to leave an imprint on your soul, then vanish before the cost of his genius came due.

I knew, we all knew, about the drugs. You couldn’t manage Roy Hargrove—you rode him like a wave and hoped you didn’t drown. The jazz agents tried their best. The body, failing; the spirit, persistent. He needed dialysis, but music kept interrupting medicine. He was already in that lineage of Miles and Clifford and Lee—not just in talent, but in tragedy. He wasn’t playing through charts or theory books. He played through life. Through the lyrics. Through the scream. His horn didn’t sound—it wept, it seduced, it confessed.

The documentary gets at this. It doesn’t offer clean answers, and that’s exactly right. It’s vérité, yes—cinema stripped bare. Roy on stage, Roy backstage, Roy alone. Friends and heroes—Herbie Hancock, Sonny Rollins, Erykah Badu, Questlove, Glasper, Wynton, Yasiin Bey—they all show up to speak the truth about a man who could never fully tell it himself. And there’s that moment. Lord, that moment—Roy quietly playing “Say It (Over and Over Again)” like it’s the final sermon of his life. And maybe it was. That scene alone is worth the whole film. A musical epitaph, whispered to the cosmos.

Hargrove doesn’t avoid the hard truths—race, addiction, genius and the machinery that tries to box and sell it. Roy wasn’t made for neat packaging. He was chaos wrapped in silk. He was the bleeding edge of hard bop, the soul of R&B, the heartbeat of hip hop. RH Factor, big band, ballads behind Roberta—he did it all, and he did it with style and swing that no school could teach.

I won’t judge the man. That’s not the role of a witness. I’m here to testify. I watched him blow holes in the sky with a horn that spoke more honestly than most poets. I was there when he moved a room with three notes. I was there when the weight of his living nearly crushed him.

But I will say this: Roy Hargrove gave us everything. He gave it before he had much left to give. And it’s all still here—in the records, the bootlegs, the grainy photos, and now, this documentary. His music is unparalleled. It stands untouched by his downfall. Like Basquiat’s paint, the pain is in the strokes, but the art—oh, the art—is divine.

I was there. Big ears. Camera in hand. Witness to a giant—one who never stopped trying to play his way out.

1992

Bill King: You were cast in the role of leader early in your career. Have the additional responsibilities put more pressure on you?

Roy Hargrove: Definitely. I make sure I keep that responsibility and the additional pressures in perspective. You have to pay attention to what each band member is dealing with. You have to make sure it all works together. As a unit, everybody has similarities, but I make sure there’s enough contrast to work as an ensemble.

B.K.: Are you able to hold on to players or attract musicians best suited for your music?

R.H.: Recently, I’ve changed the rhythm sections. I think this is the band that’s going to work. The one I had with Antonio Hart, Stephen Scott and Christian McBride was more of a group of people who did their own thing. With the new band, I have more of a group sound. You need to have the right guys who want to play and develop a group sound.

B.K.: What’s a rehearsal session like?

R.H: If we’ve played for a week, we go over tunes we’ve played before. Most of the time, rehearsals are called so we can bring in new music. Everybody contributes.

B.K.: Are there compositions that don’t make it to your live repertoire that still end up on the record?

R.H.: It’s just a matter of time. If we don’t play it now, we may include it later. We have to develop specific tunes. We learn a set of tunes and play them on the road. Once they’re down, we move on. We haven’t been working with this unit long enough for me to tell exactly how we’re going to develop that end of it.

B.K.: How much input does your supporting cast have in arranging the material?

R.H.: If you have a tune, you submit it. Depending on how the song is, we may learn it by ear. We add all the colours to it as we play. I may bring in a tune, but we might not end up playing it the way I wrote it. We may end up exploring something different from what I had intended due to someone else’s input.

B.K.: You’ve made some guest recording appearances with Sonny Rollins and Frank Morgan, among others. Are you the least bit intimidated by their presence?

R.H.: I try to treat all those situations as learning experiences. I learn from it. I don’t see it as a competitive thing. I’m there to make music and learn from a master. I don’t like to get into ego things and try to compete with somebody. It will take me years to get to their level.

B.K.: The recording process can be an agonizing experience for some players.

R.H.: For everybody. It can be agonizing for many people, especially with some of the engineers we have recording jazz. A lot of them don’t know how to do it. It’s very frustrating when they don’t get you the sounds – the instrument's natural sound. Countless engineers try to add too much to it, and it doesn’t come out sounding natural to the ears. It comes out sounding very electric. That’s not the essence of this music at all. It must sound acoustic. You have to get the sound of the room, our presence in the room.

B.K.: Do you have a choice of engineers?

R.H: Yes, I’ve been using a guy by the name of Jimmy Nichols, who’s very open-minded. Instead of just having his agenda or a ‘that’s the way it goes’ attitude, he opens up for suggestions. It may not be me who suggests something; it could be the bass players, drummer, or whoever. Regardless, Jimmy will listen.

B.K.: With all the attention paid to the new wave of young players, how do you think musicians react when the multi-national labels pull the plug if sales don’t match expectations?

R.H.: It has a lot to do with how the public responds. It also has a lot to do with how it’s marketed. They are still not hiring jazz players as they should. Many older musicians are about ten years beyond me, who have to sign deals with labels outside our country. They may make enough to do well in other countries, but that doesn’t address the situation at home.

Just look at the attention the R'n'B cats, the raps cats, and all the rest get because of video. R ’n’ B singers are a dime a dozen out there.

They need to get behind the players and the tradition. It’s impossible to play what’s been played before. We’re dealing with our experiences in life when we play.

It’s great that they're signing talent to contracts, and artists are putting out records, but it really depends on the record companies, like Novus/BMG, Columbia, and the likes, to get behind their artists. To me, Novus is the best record company for jazz. It’s a new label, so they get behind you and support what you’re doing.

B.K.: What kind of music scene were you involved in within Dallas? Were there a lot of jazz fans and young players with dreams?

R.H.: When I was there, it was slowing down. I think there are younger people interested in music now. We didn’t have that many jazz records in the house, but I loved the music. I had to go out and get what I wanted to hear. A couple of my teachers recommended some records to listen to.

When I heard my first jazz record, I was blown away. It was Clifford Brown. I tried to get every record I could after that. At 17, I had the opportunity to visit Japan and attend the Mount Fuji Festivals, which exposed me to a lot more quickly. It was humbling. Art Blakey was over here, and Johnny Griffin was on the other side. All of these incredible cats. I said, “Yeah, this is what I want to do.” I was going to a performing arts high school in Dallas, where they had a jazz ensemble. So, I came back home, finished high school, and went off to Berklee.

B.K: These programs that have been in place for the last 25 or 30 years are currently producing talent like you—Wynton and Branford Marsalis, Mike Stern, Bill Evans and so on.

R.H.: The veterans are very supportive of what I’m doing. They want to see the tradition continue and the music live on.

B.K.: With the success of Diamond in the Ruff and Public Eye, how do you feel about The Vibe?

R.H: Great. It was recorded in three days. On the first day, we did 12 tunes. This is with the new band. It jelled and was very successful. We did take after take. Branford and Jack McDuff are on it. We’ve got some grease on there, and there’s a lot of original material.

B.K.: The future?

R.H.: I want to get into production and record jazz groups. R'n'B, rap, all kinds of different music.

Incredible artist

I’ll never forget seeing him live in Toronto in the 90s in a small jazz club with old wooden theatre seats .. I forget the club’s name.