There’s a photo of Janis’s apartment on Noe Street in San Francisco—there’s a table in the frame and a Salvation Army keeper near the window. A pick-me-up chair every hippie fashioned their living space with in the ‘60s. What draws me to this frame is the fact that we both sat together, faced one another, and talked music. Janis, with her small record player and stack of 45s.

“Mr. Bill, have you heard this?”

Okay, —you will never buy this moment. You will never live it, hear it, or inhabit it. You can purchase art, store it in a vault, and claim ownership, but you can’t rent or purchase a moment like this.

Janis played acetates of songs sent to her from Jerry Ragovoy—a superb producer, a soul songwriter. Now there’s a name that rolls off the tongue like a bluesy horn line, a name soaked in the sweat and reverb of soul’s golden era. The man wasn’t just a songwriter; he was an alchemist, turning raw feeling into wax-grooved gold.

You don’t just hear a Ragovoy composition—you inhabit it. The anguish in Lorraine Ellison’s "Stay With Me"? That’s Jerry, wringing every last drop of heartache from the strings. "Piece of My Heart," later commandeered by Janis Joplin and torn apart in that Texas hurricane of a voice? That’s Jerry, carving a melody so potent that even the roughest edges of rock ‘n’ roll couldn’t dull it.

And then there’s "Time Is on My Side." The Stones may have stamped it into rock history, but Ragovoy had already laced it with a kind of deep, knowing melancholy—the sort that only a man fluent in the language of rhythm and blues could muster.

Janis explained her intentions of assembling a band in the Stax/Volt/Muscle Shoals vein, to answer her passion for rhythm & blues. I had spent the past year travelling the West Coast and as far as Las Vegas with soul quartet Kent & the Kandidates. We had a vast repertoire of East and West Coast soul, from Lowell Fulson to Otis Redding.

I told Janis about a song I loved that hadn’t been overplayed, a staple of our set—Eddie Floyd’s “Raise Your Hand.” She bought a 45 and loved it, then asked me to arrange it. Later, she performed on television with superstar Tom Jones.

How does one come from Bessie Smith to Big Brother to the Kozmic Blues Band?

I’m guessing it was over 30 years ago that Karen Gordon, then of CBC Radio, asked me to join her in a retrospective look at Joplin’s career. I went to Sam the Record Man and found a compilation of reel-to-reel coffeehouse and informal recordings that predated Big Brother. And there it was. The soul of Janis. The big bang. The roots—blues, bluegrass, country-tinged singing. A youthful voice finding its way through history, connecting the wires between inspiration and the past. The electricity that ignites and propels. The current that powers learning, dedication, and results.

Ah, the Typewriter Tape—that raw, unvarnished sliver of blues history where Janis Joplin, pre-fame, pre-stardom, pre-myth, sits down with Jorma Kaukonen and spills her soul onto tape. No big production, no swaggering Big Brother guitars behind her—just the unfiltered rasp of a Texas girl who lived and breathed the blues. And then there’s Margareta Kaukonen, dutifully clicking away on a typewriter in the background, a surreal kind of metronome keeping time with history.

By ‘64, Janis was a drifting spirit, caught between Texas and California, between folkie aspirations and the riotous, electrified explosion she’d later ride to immortality. She had that raw, Odetta-Bessie Smith-infused fire even then, but there was also a tenderness—a reverence for the blues that’s all over this recording. Trouble in Mind, Hesitation Blues, Nobody Knows You When You're Down and Out—these weren’t just covers for her; they were musical lifelines. You can hear it in her phrasing, the way she chews on each note like it’s the last drop of whiskey in the bottle.

Kaukonen of the Jefferson Airplane was already airborne when I was kicking around the West Coast scene. A meticulous, nimble player—always had that folk-blues touch, even when he swirled through psychedelic storms with the Airplane. It makes perfect sense that he’d be sitting across from Janis in this moment—two kids raised on the blues, finding common ground before the rock ‘n’ roll circus took them in different directions.

The Typewriter Tape is a beautiful relic, a prelude to the chaos and legend that followed. It’s the sound of two musicians before the weight of history settled on their shoulders, before Monterey and Woodstock, before the inevitable crash-and-burns. Just a woman and a man, a guitar and a voice, the blues and a typewriter keeping time.

When it’s this raw, it eventually thaws and blossoms into the person who was meant to be. Janis eventually becomes Pearl. It was the seriousness of the journey that shaped her. The weight of her voice, the ache of her phrasing, the ferocity of her delivery.

Sitting there in that Noe Street apartment, I could see it forming. A woman with a suitcase full of blues, a pocketful of Texas dust, and a heart that burned like a neon flame against the backdrop of a world not yet ready for her.

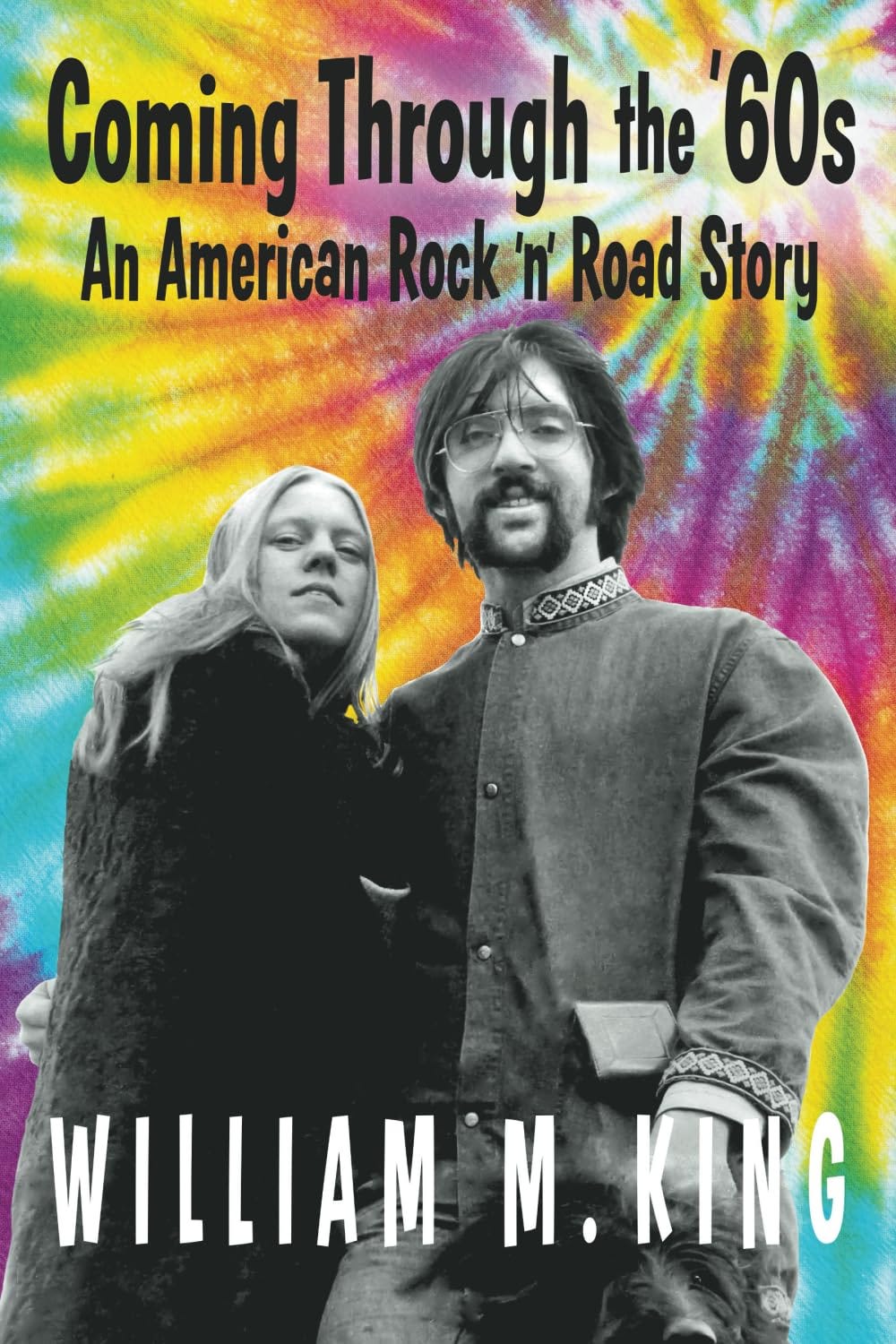

You can read the full story - Coming Through the ‘60s. Available at Amazon.

I'm WAY behind in my Bill King reading. Nuts.