I dream in grain and gauze—celluloid loops that slip the truss of time. Smoke curls up from ashtrays not touched in fifty years, the air sweet with reverb and clove, and a house band somewhere behind the scrim of memory tuning to eternity. The club names rise like incantations—Slugs, The Scene, Shelly’s, The Whisky, both Fillmore’s. Temples of tone. Places where the sound lived long after the last downbeat. Where you could still hear the echo of a Coltrane solo in the floorboards if you leaned in with the right kind of ears.

I was there. Not as a chronicler, but as a ghost in training. Calloused hands from gigging, yes—but a heart tethered by doctrine. You don’t point a lens at another soul, they said. You don't take—you listen. So, I heard. To Jimi, blowing holes in the known universe. To Janis catching fire, then disappearing in smoke. To the Dells harmonizing like velvet thunder. I stood in corners, head bowed, breath caught.

And while I stood, he shot.

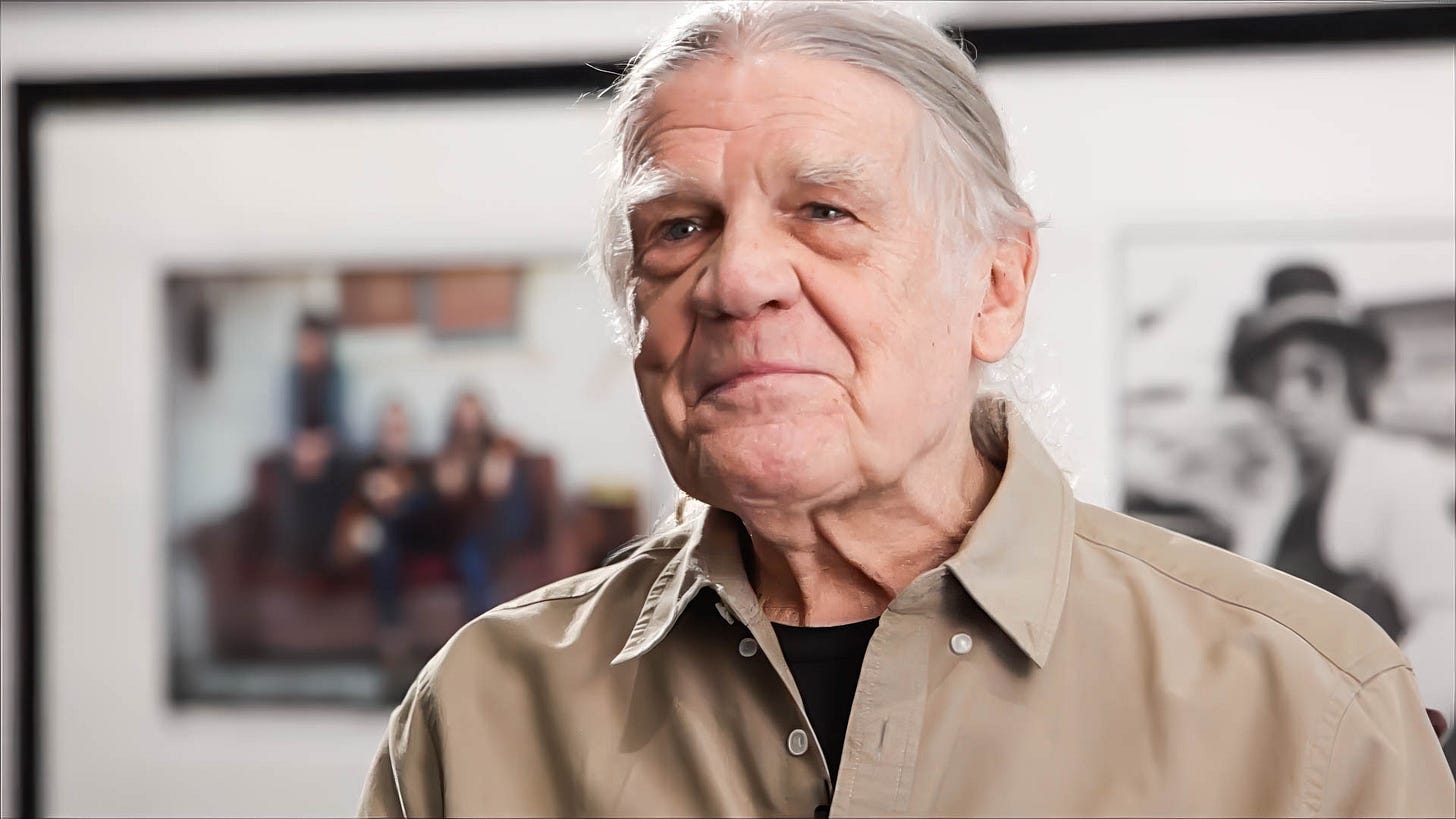

Henry Diltz didn’t wield a camera. He wore it like a stethoscope. Listening for heartbeats and catching musicians in their in-between moments—when the performance stopped and the living began. Diltz didn’t pose you. He waited. He trusted. And the world gave itself to him.

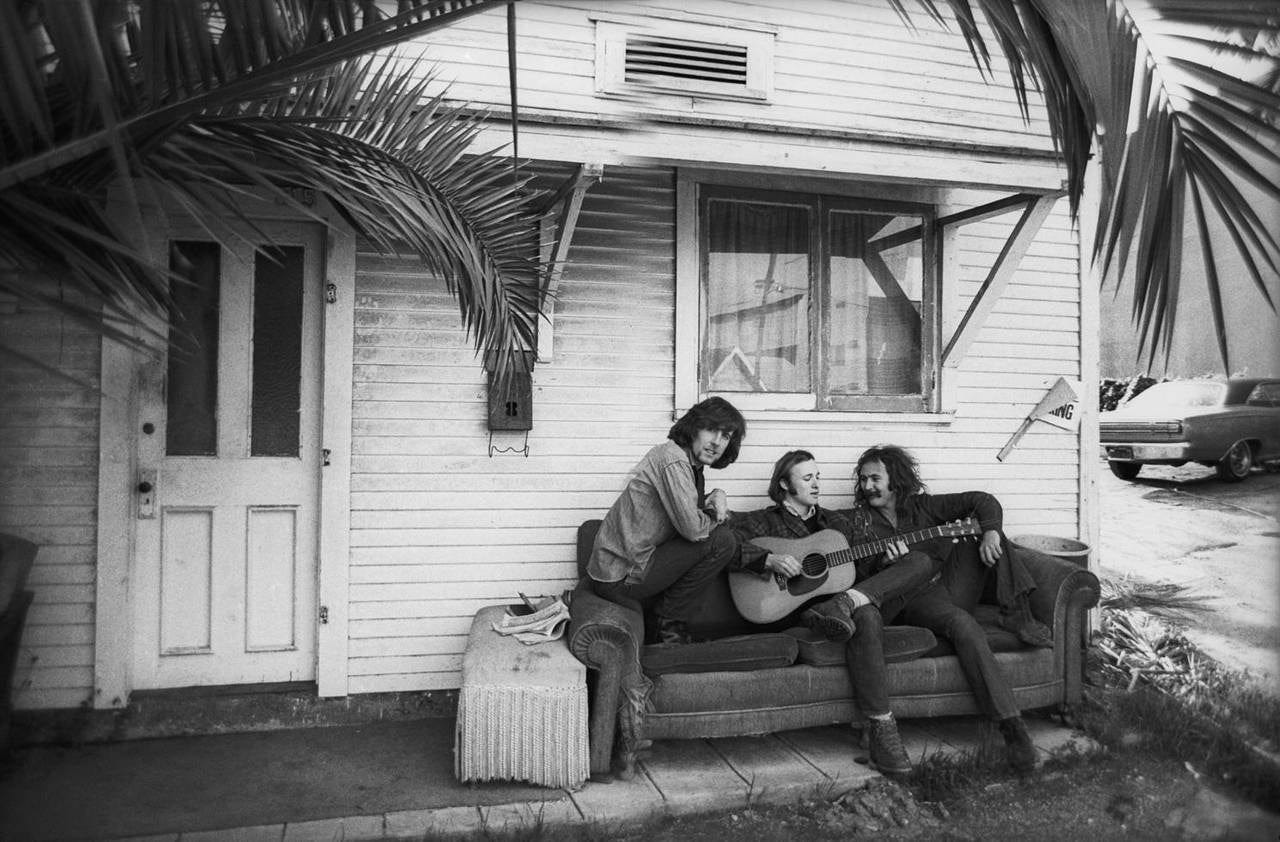

Laurel Canyon, California. Not so much a place as a mood. Golden with possibility and backlit by dusk. Diltz was there with Crosby on a porch, Stills with a joint, Nash cracking wise. There’s a warmth to his work—a suggestion of trust. These weren’t publicity stills; they were communions. A couch in front of a condemned house became an album cover that outlived the house, the moment, and eventually some of the men.

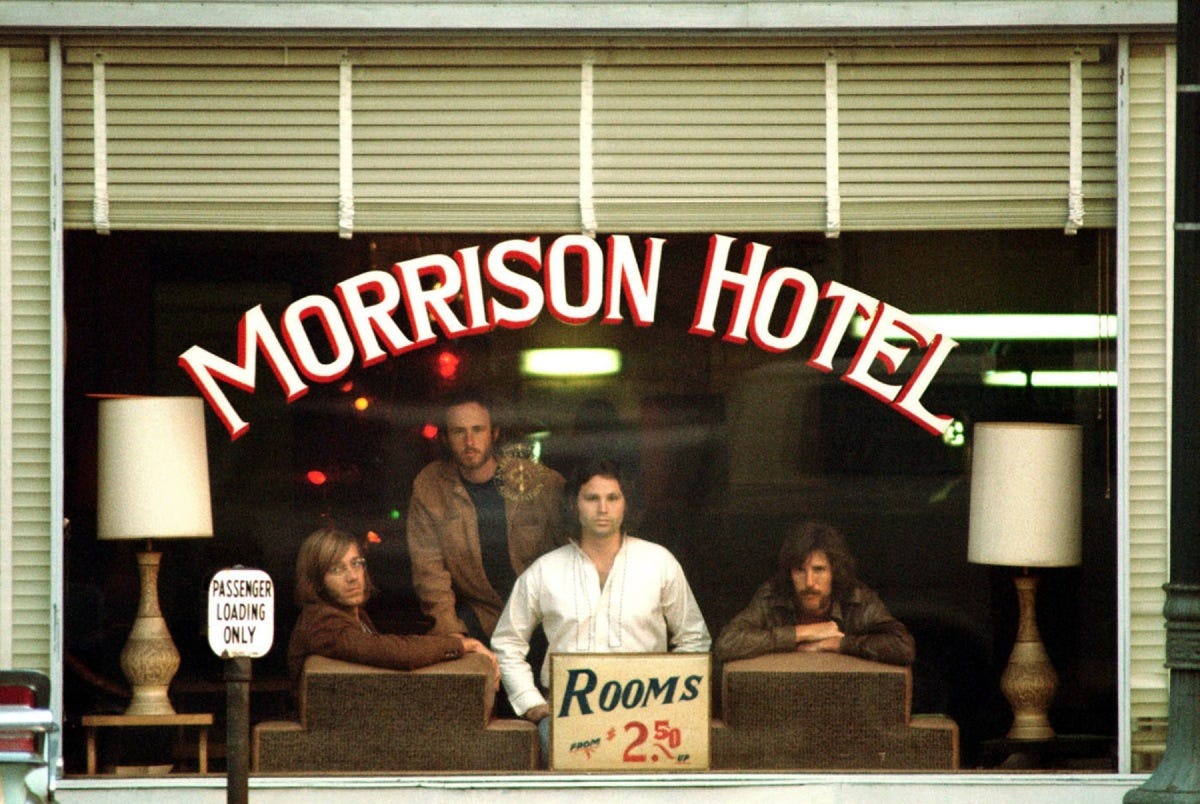

The Doors, locked in behind glass at the Morrison Hotel—waiting for a desk clerk to disappear and fate to step in. That was Henry. Waiting, watching. Knowing when not to shoot. And when to strike like lightning.

He didn’t chase the story—he lived it. Banjo in hand with the Modern Folk Quartet. An insider. The kind of man who could get Paul and Linda McCartney to lean into each other like no one was watching. Who could catch Mama Cass with her guard down, laughing over tea? Who could watch Neil Young disappear into snow and bring him back in a single frame?

I envy that.

Not just the photographs, but the audacity of stillness. I didn’t have it then. My young hands were too trained in reverence, my spirit still shackled to pews and pulpit. I feared intrusion. Believed memory was sacred and not to be pressed between negatives. But now? Now the camera is a second skin. In this third act, I am trying to catch up—not to the fame or the frame, but to the permission. The declaration: I was here. I saw this. And it mattered.

Because when Henry shot Woodstock, he didn’t just shoot a festival. He caught a country mid-exhale. When he wandered Monterey Pop, he knew the light was borrowed and brief—Janis’s ascent. Otis’s commanding. Hendrix was setting the American dream ablaze in feedback and flame. He held those images without binding them, offering history a seat in the front row.

We speak of legacy as if it were a monument. But sometimes it’s a contact sheet, curled at the edges. Sometimes it’s Joni barefoot with her dulcimer, or Jackson Browne on a couch, not yet mythic, just young and open.

Henry Diltz didn’t shoot history. He rescued it—one quiet moment at a time.

And me? I still dream in reels—the light leaks in. The clubs come back to life. And every so often, in that half-sleep hum between then and now, I lift the camera—not to steal, but to testify.

Because Henry taught us: the lens is not a weapon. It’s a witness.

Most Iconic Album Covers by Henry Diltz

Crosby, Stills & Nash – Crosby, Stills & Nash (1969)

Shot spontaneously in front of a condemned house in West Hollywood. The band hadn’t even settled on their name when the shot was taken, and the house was torn down the next day.

The Doors – Morrison Hotel (1970)

Jim Morrison and the band posed inside the actual Morrison Hotel in downtown L.A., with Diltz shooting through the glass. A classic image with gritty urban resonance.

James Taylor – Sweet Baby James (1970)

A rustic portrait of Taylor that helped define his image as the introspective, soulful troubadour.

The Eagles – Desperado (1973)

A Western-inspired shoot with the band dressed as outlaws, featuring images taken in the Mojave Desert and staged like a vintage outlaw movie.

America – America (1971)

A soft-focus, earthy tone photograph fitting the band’s pastoral, folk-rock vibe.

Legendary Candid Photos

Joni Mitchell in Laurel Canyon

Diltz captured Joni sitting with dulcimer in hand, barefoot in her home—a hauntingly poetic moment of quiet artistry.

Paul and Linda McCartney at a ranch

A warm, playful photo shoot that emphasized the down-to-earth domesticity of one of music’s most mythologized couples.

Mama Cass Elliot in her kitchen

Cass with a cup of tea, laughing at home—a perfect example of Diltz’s ability to bring out relaxed intimacy.

Jackson Browne and friends during early career days

Backstage, beachside, and couch-lounging images of Browne and the SoCal folk-rock circle.

Neil Young walking through the snow at Broken Arrow Ranch

A stark, soulful portrait that mirrors Young’s moody lyricism.

Festival Work

Woodstock (1969)

As official photographer, Diltz chronicled everything from Ravi Shankar’s performance to the muddy, euphoric crowd.

Monterey Pop Festival (1967)

Candid and electric images of Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and Otis Redding mid-ascension.

We were just kids when we started buying records and I remember very well seeing his name on so many of the records I bought. The images took us places and fuelled our imagination. We wanted more! As a kid, I remember wondering how a guy like that got to take those photos? He made it look so casual, and he appeared to be everywhere! Every time I bought an album, there he was! Years later I learned about the photo gallery (and web site) in NYC, the Morrison Hotel. One of these years, when the dust settles in the US, I'll make a trip there. Diltz has a FB page too and often posts old images he took. It'd be very cool having one of his images framed and in the house. I'd probably go for something from Woodstock. I find in these turbulent times, I'm listening to a lot of that old music again, and even picked up a few LPs. The other day, I snagged a used copy of the Morrison Hotel...