Toronto in the early ‘80s was a city of side doors. A gig town where you could play five nights, sleep three hours, and still make last call at Bemelmans if you had the stamina—or a good lie to tell the doorman. One of those doors swung open nightly at the El Mocambo, where an American expat named Billy Reed was preaching the gospel of groove.

Billy was a drummer by trade, a singer by design, and a believer by birth. He fronted a tight R&B outfit called The Street People, a band whose name alone suggested more corner sermons and curbside confessions than glitzy aspirations. They weren’t chasing the radio. They were chasing feel.

Billy had the voice of a scrapper and the timing of a prizefighter. His setlists were baptisms—Tower of Power, Al Green, Bobby "Blue" Bland, and always, always a couple of cuts by his saviour: Billy Vera.

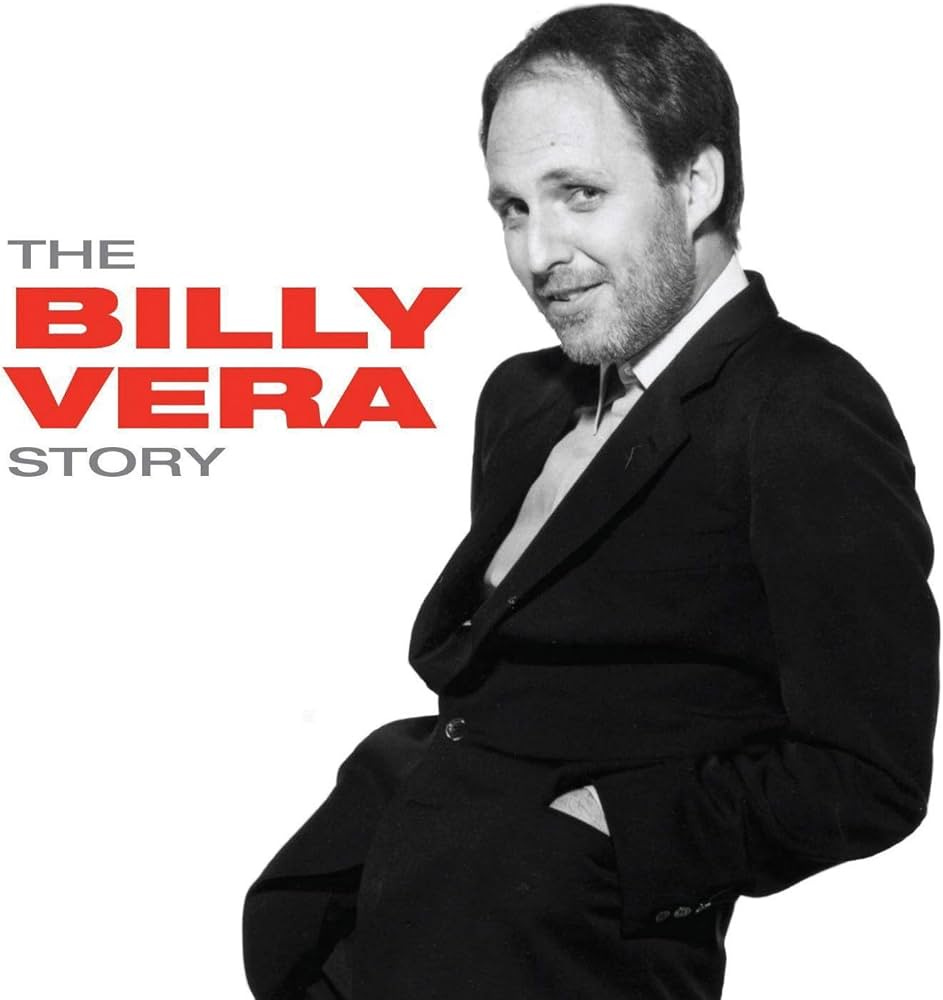

Billy Vera never chased stardom; he chased authenticity. Born in Riverside, California, but raised in the melting pot of Westchester County, New York, Vera grew up with his ears wide open listening to black radio stations when most white kids were still twisting to Pat Boone. He cut his teeth as a songwriter in the Brill Building era, a time when pop wasn’t just manufactured—it was meticulously crafted. Before the spotlight found him, he was penning tracks for folks like Ricky Nelson and Barbara Lewis, hustling around studios with nothing but a hook, a bridge, and an ear for soul. The man had the instincts of a hitmaker, but the soul of a record collector—always more interested in what was on the B-side than the Billboard chart.

Vera’s voice had that lived-in ache, like he’d been baptized in heartbreak and dried off in the wings of the Apollo. However, it was 1987’s “At This Moment,” a song that had been buried for six years before Family Ties brought it back to life, that brought him national recognition. Suddenly, the guy who had been playing every dive and club with his band The Beaters was at the top of the charts—and he did it without sacrificing a lick of integrity. Billy Vera wasn’t some pop puppet. He was a white soul man with a deep knowledge of the form—an archivist in a porkpie hat, a torchbearer for Ray Charles and Sam Cooke, and one of the few who could live in that tradition without impersonating it. When he sang, it wasn’t mimicry—it was memory. Muscle memory. Blood memory.

Billy Reed - this is for you!

I knew going in, Vera was my kind of guy. Enjoy!

Bill King: What are you going to do for an encore?

Billy Vera: I’m still moving along. I've just published my first photo book – pictures I took some years ago when I first moved out here. It’s called VINTAGE NEON: Los Angeles 1979. It’s a photo book of old neon signs accompanied by commentary; later this year, my memoir, Harlem to Hollywood, will be released. I currently have an album called Billy Vera Big Band Jazz, which I’ve wanted to do for many years.

B.K: Where would we find these?

B.V: On Amazon. I have a publishing deal for the photo book, and Hal Leonard will then publish the memoir. There’s also a documentary in the works called Harlem to Hollywood. They’ve just about finished the filming – the talking heads; then it goes into the hard part – the editing process. We’ve got some great interviews with Dolly Parton, Dionne Warwick, Mike Stoller, Nona Hendryx of LaBelle, Joey Dee from Joey Dee and the Starlighters, a bunch of great people.

B.K: You were born in Riverside, California?

B.V: Yes, my dad was stationed in Riverside at March Field and was in the army air corp during World War 11. He was a bomber pilot who taught the boys how to fly B 24s. He got hurt as they were about to go overseas. They were driving down to San Diego to ship him out when some stupid kid threw a rock through a window and blinded him in his right eye. So we were sent to Springfield, Missouri, where there was an army hospital, and my mom began singing on the local radio station – KWTO. Her guitar player was a young fellow named Chet Atkins.

After he recovered, we moved to Cincinnati for five years, where my dad had worked before the war as an announcer, and my mom became a singer on WLW, a massive station that could be heard from Toronto to Brazil and in forty states. When I started second grade, we then moved to New York. Then dad got a job as a staff announcer on NBC, where he remained for thirty years. Mom tried to make a solo career, and that didn’t work out. She learned to sight-read music and became one of the Ray Charles Singers on the Perry Como Show and Como’s records.

B.K: How would you eventually get close to the New York rhythm & blues scene?

B.V: I remember vividly, I was in sixth grade, and one morning one of the kids said, “did you hear rock n’ roll last night?” I said, “What’s that?” He said, “Alan Freed, man, 1010 Wins Radio,” so I listened to the radio that night and fell in love with rock n’ roll. As time went by, I found that I liked the rhythm and blues records and started playing around with the radio, focusing on the right-hand end of the dial, where all the black stations were. There was more music I liked there. I became captivated by that kind of music.

B.K: You could go from Maine to New Jersey those days, and the club scene was all about rhythm & blues six nights a week, and a player could work seemingly forever.

B.V: Yes, but we pretty much stayed close to home. We lived in the suburbs just north of the city in Westchester County, the White Plains area. We lucked into a job at a club called the Country House, later known as the Deer Crest Inn, which was the top club in the entire area. We’d have hit record acts on the weekends. Our job was to play two dance sets and back up the acts that didn’t bring their bands, which was most of them. It was an excellent education in (a) learning how to read music and (b) what works and what does not work in terms of performance.

I remember the first weekend we had to back up acts, and it was trial by fire. Friday night featured Patti LaBelle and the Bluebelles, and Saturday showcased Little Anthony & the Imperials, which were the two acts with the most challenging music to read. Still, we came through it, and before long, we were known as the best backup band in the whole tri-state area.

B.K: When did the songwriting begin?

B.V: I started fooling around with it at about age fourteen, and by the time I was eighteen, I began taking songs around, and the first song I ever took to a publisher got recorded by Ricky Nelson, “Mean Old World,” and it became a hit record for him. It was beginner’s luck. It was a song I’d written for this new girl singer, Dionne Warwick. I didn't realize Bacharach and David had her all tied up. That led to a staff writing job at a publisher, April Blackwood Music, and I remained there for five years. The boss said, you need a little seasoning and put me under the wing of this fellow named Chip Taylor, who was about four years older than me, and I learned a lot about the craft of writing songs from him.

B.K: Your first hit for yourself was 1987 – At This Moment?

B.V: I had national hits in the '60s, not huge, but still national. Chip and I wrote a song called “Make Me Belong to You,” which became a hit for Barbara Lewis on Atlantic Records. That gave us entrée to the top executive, Jerry Wexler. We wrote a song that we pitched as a duet for a couple of Atlantic artists, created a demo, and took it to Jerry – he liked the music and my voice. He said, get rid of the girl on the demo, and I’ll record you on Atlantic.

I was a friend of Nona Hendryx, a member of Patti LaBelle and the Bluebelles, whose voice I felt blended well with mine. She and I recorded “Storybook Children,” then the manager got involved, fearing Nona would quit the group if we had a hit. We then auditioned about twenty other girls, and Wexler suggested Judy Clay, an adopted cousin of Dionne Warwick. We liked her voice and recorded with her, and it became a hit record. We were the first racially integrated duo to sing love songs, and that is what led to our appearance at the Apollo Theatre, where we became a popular act.

We had a follow-up hit called “Country Girl, City Man,” at which point, Judy, who was signed to Stax Records and I to Atlantic, witnessed the distribution deal between the two dissolves, and we could no longer record together. Wexler found a song for me on a Bobby Goldsboro album called “With Pen in Hand,” and did a little research and found it was not going to be the follow-up single to Bobby’s big hit “Honey,” so he called me in, and I recorded for myself on Atlantic, and that became a hit. After that, music, culture, and everything else changed radically in the late 1960s. That style of blue-eyed soul singing went out of style. I had no more hits – the 70s were about survival.

B.K: You hit with Dolly Parton, “I Got the Feeling?”

B.V: I didn’t have a hit for about nine years, and then in 1978, “I Got the Feeling” got to Dolly Parton and became a #1 country hit for us.

B.K: What a great feeling!

B.V: I didn’t know what was going to happen throughout the 70s – what am I going to do with my life? I’m working these crummy clubs and playing survival gigs – trying to make a record and failing. That put me back into the business.

B.K: One of the pivotal moments in my music education was a series of box sets you assembled for Capitol Records early 2,000 – combo, cocktails, etc. “Pachuko Hop” – which we recorded with Saturday Night Fish Fry.

B.V: The cocktail combos - “Pachuko Hop’ was on Jumping Like Mad. A fellow named Pete Welding at Capitol before he died put me in charge of his blues series – Capitol Blues. I did five, six, seven, whatever it was, albums for that series.

B.K: You found some great material, and I was impressed by how deep you dug into the Los Angeles music community archives. Chuck Higgins, who recorded the original “Pachuko Hop,” lived in our apartment complex in Hollywood. He’d pack his sax every other night, show up at some event, and play his hit song, a monster hit among old school Latinos.

B.V: I’ve done a couple of hundred reissue CDs over the years, and one on Chuck Higgins for Specialty Records, and I included of course “Pachuko Hop.” I looked him up in the union and found him and interviewed for the liner notes and found out he went on to teach music at a local college here. He wasn’t much of a sax player in terms of skill, he could never be a bebopper for sure, but he played with a lot of feeling.

B.K: Kind of from that “honkers” and “shouters” era. There was also a great version with a big band – I don’t know where you found that.

B.V: That was Ike Carpenter. Carpenter is an unsung hero. I dug deep to find as many records as I could on him. He was a big fan of Duke Ellington because he recorded many of Duke’s songs during his early years. Duke is my number one or two heroes. Ike is one of the few who recorded Duke Ellington songs and got the real feeling. He got the harmonies right and captured what Ellington felt.

B.K: You did three albums with Lou Rawls?

B.V: I did four. We had a great time. That came about also through Capitol. Bruce Lundvall was running Blue Note Records by that time, a subsidiary of Capitol. He and my friend Michael Cuscuna, one of the all-time great jazz producers, thought I might be able to help when Bruce signed Lou to Blue Note. Up until that time, Lou was producing a lot of what we call “Vegas-style disco albums,” attempting to recapture the Gamble & Huff era, but not doing an outstanding job of it. His record sales were dismal. Bruce’s idea was to let’s take him back to when people fell in love with Lou Rawls in the beginning, back to his jazz and blues roots, and have him record some of my songs too. Michael and I made a good team. Each of us has different skills. Michael knows all the great musicians, so we could use some wonderful people: Richard T, Cornell Dupree, Fathead Newman, and George Benson. I’m good at song selection – working with singers and musicians to get the most out of them. It was an excellent team.

The first album we recorded with Lou, “At Last,” reached #1 on the jazz charts. We then produced two more albums for Blue Note, utilizing many of the same personnel, and all were top-five albums. Lou and Blue Note went their separate ways, and about five years later, his manager called me up and said he couldn’t get Lou a record deal, and I said, “You’re kidding?” He said they want kids - no one his age. I thought that was nuts. He asked if I had any ideas. I’m not above using a gimmick; sometimes two names are better than one, so I said, what about 'old brown eyes sings old blue eyes?” Lou Rawls sings Sinatra. He ran with the idea and still couldn’t get a deal.

At one point, I was doing a lot of reissue work for old Savoy Records, a jazz label, and I sounded them about it, and they said yes. Then I came up with an idea and presented it to Lou – if the record company is going to pay for this album, you will make a small percentage if and when they recoup their investment. I said, what if you pay for the album; you own the album and the license to Savoy. If we record “Come Fly with Me” and American Airlines doesn’t want to pay for the Sinatra version, they can get the Lou Rawls version for a lot less, and then you can make all that extra money. He thought that was a good idea.

Lou financed the album. We went into Capitol’s big studio A, where Sinatra, Dean Martin, Nancy Wilson, and Nat Cole made all of those classics. Even with Savoy’s not-excellent promotion skills, the album remained on the jazz charts for six months. Lou died not long after that.

B.K: Billy and the Beaters?

B.V: Still working the Beaters in southern California when we can. I also perform with the big band and am having a great time with that. It’s a big eighteen-piece band. I have some of the finest jazz players in L.A. willing to play for the little money I get.

B.K: You must feel the radical technological shift, the dwindling dollars in CD sales, and the rise of streaming?

B.V: I do sell online with iTunes. It depends on the style of music you’re selling. I think teenagers don’t care about CDs or albums, but many are becoming interested in vinyl again. My audience is older and wants something they can hold in their hands – read the liner notes, etc.

B. K: Through all the years working with singers and being a terrific singer yourself and coming across a voice with great potential, what advice do you give them?

B.V: The most important thing is to believe them when they sing. You get a guy like old blues singer Jimmy Reed, who had a range of about six notes, and you believed every word he sang. In that sense, he was a great singer. He didn’t have the power of a Patti LaBelle or Aretha Franklin, but he had that believability – that soul, that feeling – the ability to express emotion without sounding phony.

I had the chance to meet and work with Billy in Vancouver in the 80's when he came up to Van to star in a show called Wise Guys,my band The Belairs acted as his back up band as Billy mimed one of his tunes on the Commadore Ballroom stage,lots of fun and Billy was a very kool gentlemen and class act.....l.c.smith gibsons bc