It was 1986. Q107. Sunday morning. Q-Jazz.

I was still raw—green behind the mic, nervous as a street busker handed a tux and told to conduct the Philharmonic—my first real gig in radio. Up until then, I scripted every breath. Live? Forget it. I was terrified of the sound of my improvisation. Please give me a piano. A chart. A downbeat. But don’t leave me alone with a hot mic and expect coherence.

Then came the call.

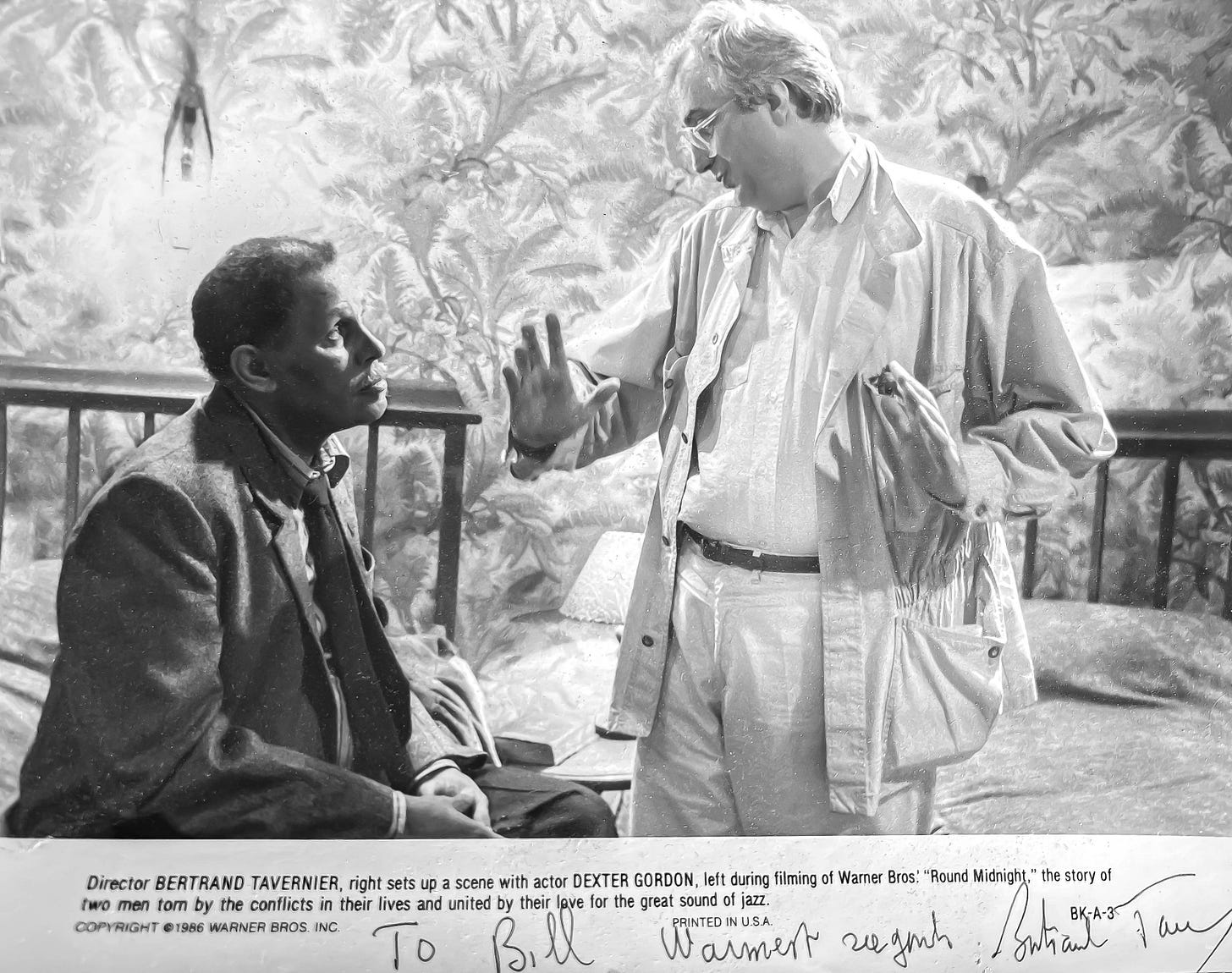

Jayne Hawtin. Towering presence. Our news director. A pioneer in broadcasting, in the mode of Linda Ellerbee, a woman with sharper elbows and zero margin for sloppiness. “You’re our jazz guy,” she says, like that settled it. “French film director Bertrand Tavernier’s in town. Wants to talk about his new film. 'Round Midnight. It’s about a jazz saxophonist.”

I said yes before my knees could vote no.

Tavernier—at that moment, just a French guy with a movie I hadn’t seen. No Wikipedia, no YouTube primer. I bolted down to the local repertory cinema, caught the screening, scribbled notes by flashlight, and figured I’d jazz my way through the rest.

The film? A dreamy, melancholic hymn to expat musicians and the smoky after-hours clubs of Paris. Dexter Gordon haunted every frame, part ghost, part beatified survivor. Herbie Hancock’s score fluttered beneath like a heartbeat just shy of giving out. I was moved. I had questions.

What I didn’t have was a clue who I was interviewing.

No deep dive into Tavernier’s canon—no understanding that this man was France’s cinematic conscience. A post-war moralist in a trench coat. Scorsese with more poetry and less coke. Tavernier was a film critic, cinephile, historian, and director of such grace and gravitas that he made other auteurs look like graffiti artists on film’s cathedral walls.

And there I was, cassette deck in hand, in his hotel suite, jazzed and jittery, while the man answered phone calls in French and sipped espresso like a philosopher on break.

I was all Herbie this and Dexter that, rolling through my questions like I was playing a set at a local bistro. Tavernier answered politely, quietly, with that gentle air of someone who knew far more than he was letting on.

Then it was over.

I got home. Ran a hot bath. Placed the recorder on the tile. Pressed play. And then… the carnage.

Every other breath out of my mouth was, “Right, right, right, right.”

I couldn’t shut up. I’d been so determined to show I knew something, anything, that I trampled all over the man’s eloquence. Tavernier spoke in paragraphs—I responded like a malfunctioning metronome. I fled the bathroom, rewound the tape, and cringed my way through it again. “Right, right, right.” I sounded like a jazz parrot in a panic attack.

At 1 a.m., I waited for Larry King on Westwood One. I needed a teacher. Larry came on, tossed out a question, then—blessed silence. He listened. He shut up. I wanted to punch myself.

Next morning, I slinked into Jayne’s office like a scolded dog and handed her the tape. “Sorry,” I mumbled. “I blew it.”

A few hours later, she calls. “Good job. Got a couple great quotes. By the way, I’ve got a line on Miles Davis—want to interview him next week?”

I didn’t hesitate.

“Fuck no.”

Miles would’ve chewed me up and used my bones as a doorstop.

But that was the beginning. My baptism in broadcast. My clumsy first steps as an interviewer. Since then? Over a thousand interviews. The sweat has dried. The instinct now is to ask the question, then shut up. Let the story breathe.

And Bertrand? He deserved better. I wish I could go back and do it again, this time with the reverence, the patience, the silence he earned. But you only get one first time. Mine was with a master.

And somehow, even under the weight of my rookie stumbles, Tavernier gave me a gift: a seat at the table of the artists and, in the mail, an autographed picture. Not bad for a guy with a cassette deck and a pocketful of “rights.”

Right on.

What a start.