August 1998

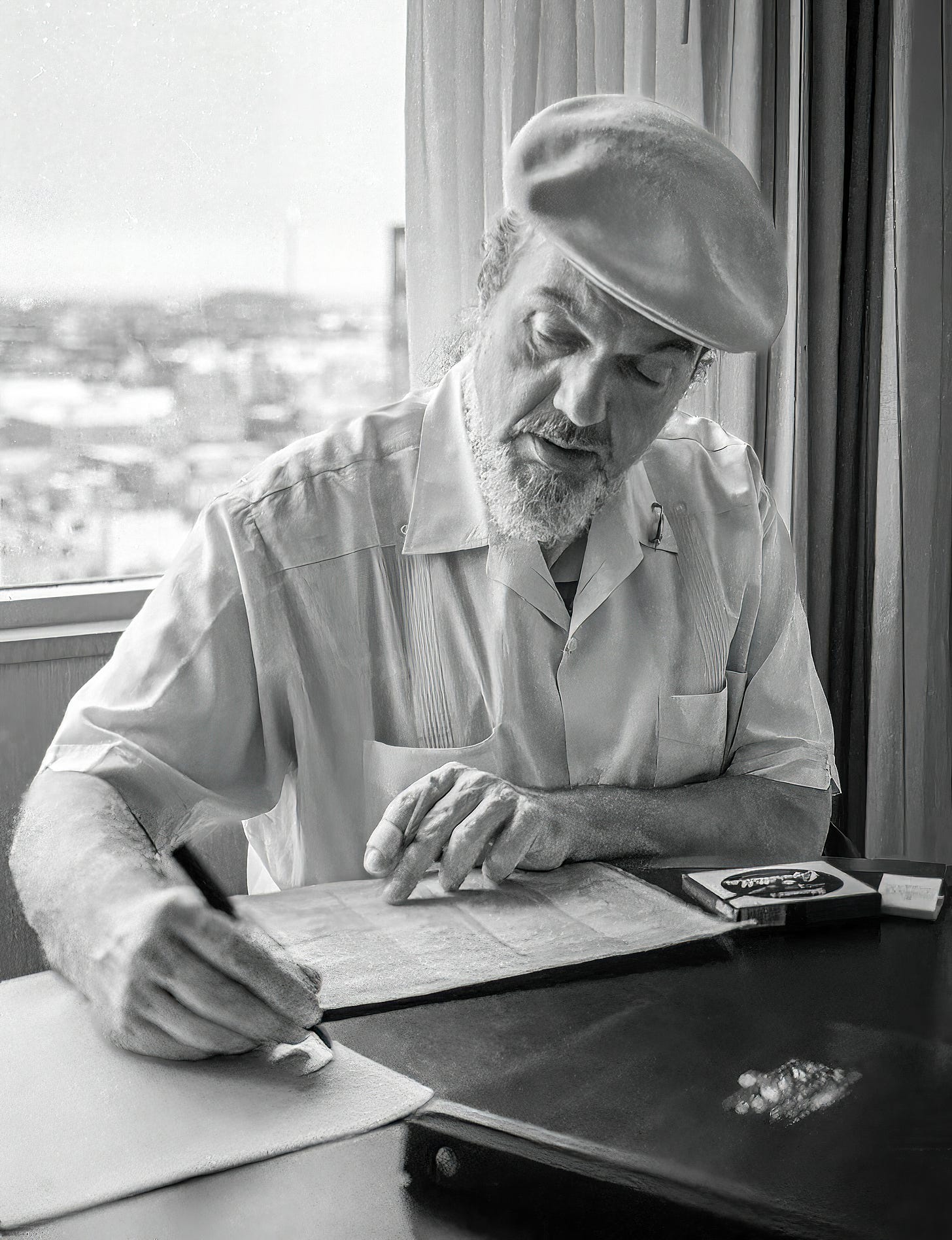

There are times you remember not by the sound of a voice or the precision of words, but by the atmosphere—by the perfume of a Sherman cigarette curling its way through stale air, a pad of paper dotted with voodoo hieroglyphs masquerading as a setlist, and the quiet tap-tap of a Number 2 pencil orchestrating the next conjuring.

Dr. John—born Malcolm Rebennack in the cradle of American rhythm, New Orleans—was more than a musician. He was a walking gumbo of spirits, jazz, gris-gris, street sermons, and syncopated mystery. When I met him twenty-seven years ago, he was deep in the ritual. Not grandstanding and not sermonizing and just scribbling a groove into existence. The man didn’t perform sets—he cast spells.

I’ll admit, I was jittery walking into that room. Not because of celebrity—Doc was never the type to polish a halo. It was because I knew I was stepping into a liminal space where sound became spirit and spirit demanded respect. And yet, the moment I saw him hunched over the pad, lips wrapped around that thin cigarillo, hat dipped just low enough to obscure the hoodoo flicker in his eyes, I felt strangely at ease.

He looked up, clocked me with a glance that seemed to read my aura and record collection, and said, “Man, you ever notice how some chords just know too much?” That broke the ice.

We talked, sure, but what we did was commune. Topics ranged from the black-magic bounce of New Orleans streets to the bad deals and blessed breaks that shaped the chessboard of American music. We both knew A&R once meant artist and repertoire—not some Armani-clad executive poring over streaming stats, but a man (or kid) who could spot fire in a bar, corral the band, book the studio, and make wax that mattered—for sixty bucks a week and a shot of luck. Doc was that kid at Ace Records at 14.

Bill King Photography

By the time the ‘60s rolled in, he'd already lived more lives than most mortals. Shooting sessions with Frank Zappa, channelling weird gospel with Phil Spector, ghosting through the smoky corners of Sonny and Cher’s studio time—until Gris-Gris dropped like a swamp-brewed thunderclap and the world met Dr. John, the Night Tripper.

But that day, it wasn’t the myth I met. It was the man. The musician is still chasing tones that never quite sit still. The poet of the piano, who believed music could divine more truth than most men ever could.

He passed me a chord chart before I left—somewhere between G7 and the second line of eternity—and nodded. “This here’s what I call a ‘maybe.’ You play it when nothin’ else makes sense.”

And Lord, wasn’t that the whole deal?

Have you ever sat with a man who is the music? I have. Once. That was enough.

Bill King: In your biographical notes, you state: “I don’t wanna know about evil. Only the delicate balance of “anutha zone,” way past Shapaka Shawee, more ancient than the olive tree. Before Rosacrucian mysteries, or Freemason vestries.”

Dr. John: It’s right where we settin’ at, you know. I know about evil. I’ve lived in this racket, the music industry, where you’re comin’ up with gangsters and whorehouse gamblin’. I know about that evil stuff. If you walk down Spadina, where any of those music joints were, they were dealing narcotics. Well, I don’t want to know about that. I’m about feelin’ some good things today. I want to feel love and feel good.

B.K: You say, “The ‘spirit kingdom’ is more powerful than just this meat world.” Have you had experiences that have brought you into contact with a supreme being or spirits from another world?

D.J: The sense of breathin’ puts me in touch every day with the ‘spirit kingdom.’ If I wake up today, I’m breathing, and I’m happy. If I can pinch my meat (pulls the skin on his arm), I not only know that I’m alive, but I’m feelin’ something. I not only know I’m alive. But I’m feeling something.

When I had the church in New Orleans from 1967 to 1989, I saw many things like cures being done. Things that I couldn’t explain. I saw a Mother, Catherine Seals, who looked like a dead baby back to life by grabbing something out of the child. I don’t try to understand or figure it out ‘cause if it ain’t broke, why fix it.

B.K: You grew up in New Orleans’ Third Ward, which was reasonably integrated. There were Afro-Americans, Cubans, Germans and Irish, along with Caribbean immigrants. When did your ancestors arrive in this community?

D.J: I know my family is supposed to be from the Bas region of France. They arrived in New Orleans in 1813 or 1830. They had a place on Bayou Road, now Governor Nicholas Street.

My great, great, great aunt Pauline Rebennack was involved with a guy who had my name, Dr. John. He was a ‘banbera cat,’ and they had a whorehouse out by what they call “Little Woods” in New Orleans.

Bayou Road was a historical street in what they call the Treme area of New Orleans today. Jelly Roll Morton grew up on that street. The one thing the Third Ward was famous for was that Louis Armstrong was born there. Unfortunately, the politicians in New Orleans decided not to keep his pad a tourista spot and tore it down. It’s a movie equipment store now. That’s typical political stuff.

B.K: Did the composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk profoundly influence the evolution of New Orleans music after he visited Cuba in the mid-1800s?

D.J: Louis Moreau Gottschalk studied with Chopin at that college in Paris and became a hit in the area because he wrote all the folk songs.

Not only was he the first classical composer of the United States, but, in his day, he was regarded as the fastest piano player alive. In his music written before the Civil War, you can hear all the elements of the samba, the rumba, the habanera, the tango and a lot of the elements of what came to be known as ragtime.

When Van Dyke Parks turned me on to this cat, I heard a piece Gottschalk wrote called "Bambula: Danse des Negres." It was about his memories of livin’ on St. Ann's Street across from Congo Square where the slaves used to do their shuck gris-gris thing for the slave masters or what they do in Haiti today for the touristas. You can not only hear the Yoruba influence but also how it was already Caribbeanized in a way.

When I recorded one of his pieces, "The Litany of the Saints People," on Goin’ Back to New Orleans, we had the number one record in Haiti, Nigeria, Brazil, and Greece. They all knew the piece, whether it was the Orisha people from Brazil, the Chango people from Jamaica or the Santeria people of Cuba.

People cried to it because we put strings on it as Gottschalk wrote. It was a tribute to him, but also a piece I’d heard in church with just guitar and a bunch of drums.

B.K: The Brazilians have also had a profound influence. Can you pinpoint a specific rhythm pattern or harmonic consideration that was absorbed into local music culture?

D.J: The Second Line rhythm in New Orleans is connected to the Brazilian samba. It’s just a little different. Cuban rhythm is in the centre of the beat, the Brazilian rhythm is a little more ‘round the beat, and in New Orleans, it’s all around the beat, pullin’ it. That’s where funk comes from, just implying the rhythm of the samba.

For the last 40 years, I’ve played the Mardi Gras in New Orleans, so I never get to see what it’s like. I’d love to go to Brazil to see all the samba clubs. It’s a fascinating connection of rhythms we play.

You know, the Cubans’ first entry into the United States was New Orleans. Most of them came through our ports. The ones who stayed kept their things intact and added something to New Orleans things.

B.K: New Orleans had three opera houses in the 1800s. Where else did you find that in America at the time?

D.J: A good friend of mine, Teddy Gumpus, was one of the guys whose grandfather started unions in America, played in 1920 in the old French Opera House. When I came up in the ‘60s, it had burnt down and was then a strip joint.

In the 1920s, Teddy sang Pagliacci at the opera house. He was famous for doing Popeye the Sailor Man. I forget what instrument he plays, the oboe or something, but he played the melody on the original tune "Popeye."

The good doctor passed in 2019 at the age of 77.

B.K: Dr. John: The Night Tripper was based on a 19th-century doctor. Who was this person, and why did you adopt this persona when staging your first tour?

D.J: The original Dr.John was a banbera cat from Africa. My name is Malcolm John Michael Crow Rebennack, so John is my second name. My Gris-Gris name is John Gris-Gris John.

Now, since I retired in 1989, I can put those things out there. It was a natural adaptation and the fact people call me ‘professario’ or ‘doctor.’ There were certain jackets hung on me, typical New Orleans stuff. People call me snake; others call me crow. I think the Dr. thing hung on because I like to read a lot.

B.K: You’ve written a piano book that delves into turnarounds and embellishments, essential to this music. How did that come about, and is it still in print?

D.J: Happy and Artie Traum wanted me to send a paper to my manager, permitting them to reissue the thing. I’m grateful to have met so many piano players worldwide who say the book has helped them. I’m also happy about preserving it on CD ROM.

For New Orleans players like Huey Smith, James Booker, Allen Toussaint, Art Neville, Professor Longhair, who I learned all kinds of turnarounds from, they were their signatures.

Other guys like Pete Johnson of Kansas City or Albert Ammons in Chicago had different kinds of turnarounds. But New Orleans had variety. I could tell which guys played on sessions by some of their turnarounds.

B.K: What’s ahead?

D.J: Right now, I want to spend some time fishin’ before it gets frostbitten cold.

Special thanks for this one, Bill. Two quick stories: I first heard him at a long-gone tavern called the Rondun (at the intersection of Roncesvalles and Dundas, a few blocks south of Bloor in the west end of Toronto); can't tell you when, but a LONG time ago! Secondly, he was inadvertently responsible for a major fight with my then brand new wife. We were on honeymoon in New Orleans, and at the jazz festival my dear friend Dick Waterman, who knew Mack well, arranged it so I could take pictures of the good doctor with Donna. And so I did, but when I went to get the pictures developed (remember those days?) I discovered there had been no film in my camera....she was, to put it mildly, pissed off!

Every home needs a little love and a Dr. in it.Last time I saw the Dr wsa 2009 with the Lower 911 and the Neville Brothers,let the goodtimes roll indeed,this was at the River Rock Showroom in Richmond BC, must have been a real trip meeting him Bill.